Ecstasies of Logic: Reflections on van der Laan's Abbey at Vaals

/

The second reason I traveled to the Liturgy and Sacred Space conference at de Tiltenberg in the Netherlands was the opportunity to visit churches designed by Dom Hans van der Laan, his family, and his students. The culmination of this pilgrimage was a two night stay at his masterwork, the St Benedictusberg Abbey at Vaals.

In addition to celebrating the Feast of the Dedication of the St John Lateran Basilica and participating in praying the monastic offices, I had time to carefully consider a significant portion of the architecture. I also spent time in lectio, completing Hans Urs von Balthasar's Love Alone is Credible and re-reading parts of van der Laan's The Play of Forms. This post is intended to be more personal reactions to that experience than critical architectural response, though for me the two are probably not too far apart.

This was a foundational formative experience, and it will take a long time to fully internalize it. But here are a number of rough reactions, part thematic and part chronological.

You can also see the complete set of photos from the Abbey on flickr.

+++ Architectural Doubts

One of the aspects which helped draw me into the Catholic Church was a nascent impression of a profound perfection in the link between the liturgy and creative work. I was near the end of an artistic youth, where faith in creativity was ready to come crashing down. My initial responses to the liturgy were purely artistic impulses, which was fitting, but I soon learned the importance of "seeing" in relation to "making" and my appreciation of the liturgy continued to grow.

When I discovered Dom Hans van der Laan's book Het vormenspel der liturgie (published in English as The Play of Forms: Nature, Culture and Liturgy), it was as though my process of engaging and conforming to the liturgy (and especially its formal elements) suddenly had a full and complete textual expression. That I would find resonance with the liturgical reflections a monk-architect is probably not surprising.

During my Master of Architecture work, I turned to Dom Hans van der Laan's remarkably complete treatise on architecture, De architectonische ruimte (Architectonic Space), and began an ongoing attempt to comprehend through application his architectural theory. This is backwards from the publication order of these two books and how most architects become acquainted with van der Laan, but it is more consistent with the schema of his own thought as a whole. My interest in his thoughts on architecture was dependent upon the place he gives architecture in the entire order of human and divine activity. A constant complaint within my architectural experience is its exaggerated self-importance.

So although I have read van der Laan's texts and have come to accept them and submit myself to them as a student indirectly, this says nothing of his own architectural output. He does not use his buildings in his texts; the only examples are archetypal theoretical spaces and unquestionably canonical works: Stonehenge and Hagia Sophia in particular. And he was clear that his particular architecture was not the only expression of his theories, only an attempt for their most pure expression and dependent upon current building methods. His theories are more like discoveries than assertions; they are descriptive not prescriptive. The plastic number itself can be derived from no fewer than a dozen approaches and recognized, if obscured, in a wide range of buildings.

So I approached the particular architecture expression with appreciation from photos but also with some doubts. It could be so purely architectural that the liturgy might be obscured. It could also be so purely intellectual as to lose its chance at a wider relevance.

I find very troubling the idea that a particular architecture would require a certain degree of intellectual comprehension or be appreciated only by an intellectual elite. Especially when it is an architecture for liturgy. The prominence of intellect in van der Laan's texts and the apparent visual similarities with other rational/abstract modernisms prompt this doubt. The discussion at the conference at the start of this trip reinforced this second doubt. There seemed to be a fairly even split in the attendees between appreciation and distaste. And the split seemed to exist within individuals as well.

Romano Guardini's description of the qualities of the liturgy—which in his work The Spirit of the Liturgy provides the conclusion and verification of Catholic liturgy—comes to mind again as a criteria for liturgical architecture. It references this exact problem.

“[It] must be simple, wholesome, and powerful. It must be closely related to actuality and not afraid to call things by their real names. In [it] we must find our entire life over again. On the other hand, it must be rich in idea and powerful images, and speak a developed but restrained language; its constructions must be clear and obvious to the simple man, stimulating to the man of culture. It must be intimately blended with an erudition which is nowise obtrusive, but which is rooted in breadth of spiritual outlook and in inward restraint of thought, volition, and emotion. And that is precisely the way in which the prayer of the liturgy has been formed.” Romano Guardini, Vom Geist der Liturgie (1918)

It is an all but hopelessly impossible criteria, which is part of why it is good as a measure.

[For what it's worth, van der Laan explicitly rejected Guardini's text in its treatment of play and the liturgy. To me it seems the dispute was one of relative importance and semantics, with van der Laan not wanting his own use of "play" to be conflated with Guardini's. Though different in character, the essences of both men's approach to the heart of liturgy are quite compatible. In particular this criteria by Guardini does not address the disputed play concept (which is more a means to understanding, not a definition of liturgy) and therefore is not invalidated in discussing van der Laan.]

+++ The Sublime

In brief, having lived for a short time in the life of the Abbey St Benedictusberg, my doubts have been quieted. There were moments where every aspect of my being was simultaneously engaged; it was emotionally and intellectually overwhelming. I have not experienced anything like it in any built environment and can think of no better attribute than "sublime."

Without going into a thorough discussion of a word we have essentially abandoned (to our own impoverishment), I will simply explain why I use the word in response to this experience. Kant wrote, "we call that sublime which is absolutely great," and related it to the quality of "boundlessness." With regard to form embodying the Sublime, it might be better to think of it as a quality which exceeds the bounds of form. It is related to that "other-than-ness" sought by proponents of spirituality in architecture. The Romantics used images of the more awesome phenomena of nature to demonstrate the Sublime, and in that vein I am very reluctant to ascribe the attribute to a work of human hands. I suspect it is impossible for a human work which does not ascend to the liturgical form-world (see below) to embody the Sublime, though perhaps cultural works may suggest it or depict it.

Alternatively, using the terms of Guardini's criteria for the liturgy, the Sublime is "simple, wholesome, and powerful": simple in that it does not speak encrypted and wholesome in that contains more of reality (Truth) than we easily grasp and therefore nourishing/purifying in rumination. And above all, the Sublime is powerful, with sense of grandeur that leads beyond whatever is recognized as Sublime. It may be the only thing that can answer the paradox of being "clear and obvious to the simple man, stimulating to the man of culture." The impact of awesomeness and grandeur inspires a visceral reaction

There is also a question as to whether or not the Sublime and the Beautiful are mutually exclusive. In some arguments, the Beautiful is what inspires pleasure and the Sublime inspires pain. I can appreciate that some would not consider this building "beautiful," if we define the beautiful as that which gives pleasure (in the more subjective sense). But that is an insufficient conception of beauty, and more so if it is bound to particular cultural conventions.

If Beauty is rather the perceptible manifestation of Truth, and Goodness its narrative unfolding, we have no greater model of Beauty than the Incarnation. The Incarnation begins with an absolute humbling and climaxes with hideous humiliation, both of which are required for the beauty of the entirety.

"In the first place, the text of Isaiah supplies the question that interested the Fathers of the Church, whether or not Christ was beautiful. Implicit here is the more radical question of whether beauty is true or whether it is not ugliness that leads us to the deepest truth of reality. Whoever believes in God, in the God who manifested himself, precisely in the altered appearance of Christ crucified as love "to the end" (John 13:1), knows that beauty is truth and truth beauty; but in the suffering Christ he also learns that the beauty of truth also embraces offence, pain, and even the dark mystery of death, and that this can only be found in accepting suffering, not in ignoring it." Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (now Pope Benedict XVI) in a 2002 message on Beauty

+++ The Intellect

The word "intellect" is pivotal in Dom Hans van der Laan's The Play of Forms. He uses the term to describe the essence of culture. It would be helpful to give a summary of his cosmology:

"We are created as one of the material beings that compose nature. Through our intellect, however, by which we rise above the conditions of matter and thus transcend time and space, we form a separate entity, within nature, that must maintain itself by means of a culture that it itself brings into existence. Furthermore, through our faith we belong to a still higher world, which transcends both matter and intellect." Dom Hans van der Laan, The Play of Forms 4

And on the forms of that still higher world:

"But as soon as human beings turn collectively to God specific external forms become necessary, just as when people exchange ideas among themselves. ... In our collective communication with God, the great real image of the creation represented by the cultural form-world acquires an independent existence as a supreme sign, which we call liturgy." Dom Hans van der Laan, The Play of Forms 29

There is much more concerning the types of forms within the form-worlds and the nature of signs for communication, but the outline of the three form-worlds and the particular reason for liturgical forms will suffice for this discussion.

Reading the chapter on cultural forms in the Abbey, what stands out is the breadth of human actions and attributes he collects under the term "intellect." Or, to put it simply, he is talking about intellect not intellectualism. It does not have the limited rational scope of a modern/humanist/academic concept of intellect; it is the more holistic humanity properly placed as seen from a monastic perspective.

It strikes me that the intellectual emphasis on number, proportion, and eurythmy has far more to do with the creation of the space than its use or appreciation. If it works, the plastic number works precisely because it gives access to what is inherently part of nature and encoded by culture. It is not like a prescriptive alchemical gnostic proportional system; its effect is preconscious.

Thus it is like the paradoxical Alban Berg quote, wherein he recognizes the same ability for intellect to surpass itself:

"The best music always results from ecstasies of logic."

I say all of this with the caveat that this is monastic architecture and not parochial architecture. This is a monastic church, and what that means relative to the rest of the church will be considered throughout this reflection. The intellectual comprehension required for van der Laan's theories is not required for his buildings; but if approached with that comprehension, the architecture in its purity and austerity, just as the monastic liturgy in its purity and austerity, is an essential component of the church catholic.

So we cannot approach this architecture as a universal formal model any more than we can expect everyone to be called to a monastic vocation.

This is the most pure expression of the van der Laan's theories on liturgy and architecture, but that does not mean it is the most complete. That is a challenge which may never be achieved.

Dom Hans van der Laan did not design a completed parochial church. Whether this was by choice or a result of a lack of commissions I do not know. Either way it seems fitting with this point of view. But he did have a hand in countless churches through his collaboration with his brother Nico, his work as a consultant (for example, he coached van Eyck in his design for Pastoor-van-Ars, Den Hague), and via his students at the diocesan course in church architecture he directed and taught.

These churches exhibit more of the literal "richness in idea and powerful images" (back to Guardini) we expect, if not require, in parish churches. Though it is worth noting that the Abbey Upper Church does have exquisite and well-suited images as well, which get lost in documentation of the architecture. Three images by Theodore Stravinsky can be found in the aisles of the Upper Church, including this Transfiguration.

And these are not afterthoughts or concessions. Stravinsky worked closely with van der Laan and on many of the Bossche School churches. And their placement is obviously carefully considered in relation to the whole.

+++ Arrival

I arrived at the abbey before Sext on a cold fall day, entering suddenly into low mountains and tall forests gold and red with a damp fall.

Despite some language difficulties, the Guestfather welcomed me, showed me to my room. The reception fall with the porter's office and "Spreekkamers" opens directly into the atrium with access to the crypt below and the church above. A side door leads into the cloister itself. My host monk also explained the half-dozen prayer books–in Latin and Dutch and most printed for the abbey specifically–that would be used during the stay.

I was given a key to the cloister as well. After so many locked churches on the drive between Haarlem and Vaals, this was a welcome image:

The Gastenkammers (guest rooms) are on the ground floor of the older Böhm building–or at least the ground floor of that wing, for the group slopes dramatically from the church at the top to the far end of the Böhm building. Each of the cloisters is at a different level: the upper cloister at the level of the But this gives the guests immediate access to the gardens and woods.

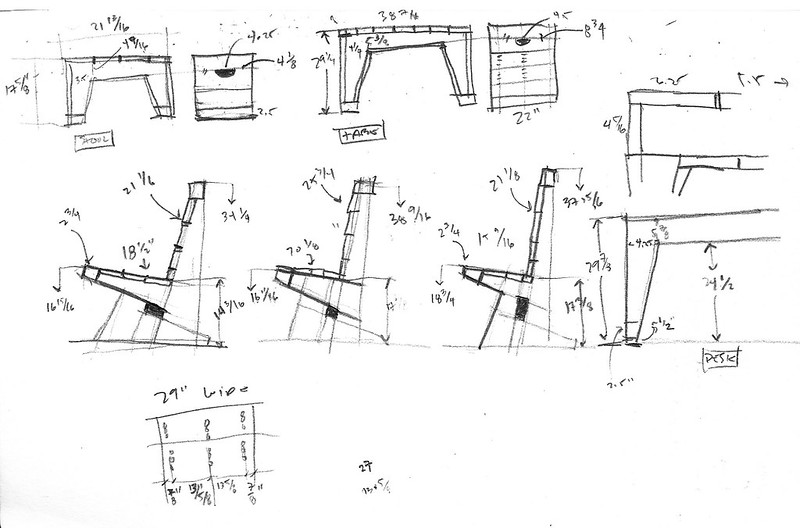

The rooms are furnished to the design of Dom Hans van der Laan: a bed, a cabinet, a writing desk, and two chairs in a muted olive-green. The furnishing throughout the abbey conforms to this one system, varying in color and measure as required by function. The chairs are an excellent example; there are three (non-liturgical) chair forms. In keeping with the plastic number, the three versions are only just past the point of intellectual distinction by sight (so that they must be based on adjacent forms), but in use they are clearly distinguishable. At the desk in the rooms is the working version and next to the bed sits on of the "reclining" type. The third "standard" type can be found in the Gastenzaal. They are also clearly distinguished by the space in the side: long for the "reclining" type, tall for the "working" type, and square for the "standard" type.

Evidently the furniture was very exciting for me. Analyzing it constituted a significant portion of labora time, as the opportunity to occupy it was rare and there many variations to compare. The usefulness and comfort of furniture based on the plastic number could be a critical test of the theory of the plastic number, or at least its application in this case and at this scale.

I found the furniture in the guest room to be extremely comfortable and perfectly suited to its respective function.

+++ Devotion

Then to the crypt. This is the principal public devotional space of the abbey with the tabernacle, side altars for individual masses for the monks (and occasional masses in Dutch), and two confessionals. The focal wall bears the names of the founders and supporters of the monastery buried therein, carved in the ubiquitous face.

The tabernacle occupies the prominent altar (directly below the altar of the church above) and is the principal focus of the crypt.

I found this space less immediately effective than most of the monastery, though with use it opened up. Like devotions should be, the space is patterned after the liturgy, but has further pockets in which to become engaged with particular aspects. Therefore the strongly ordered linear space becomes rich with the overlapping complexity of specific uses.

I expected this to be the most architecturally inspiring/significant space based on what many people had told me, but the Upper Church with its liturgy was by far more impressive.

+++ Principal Work

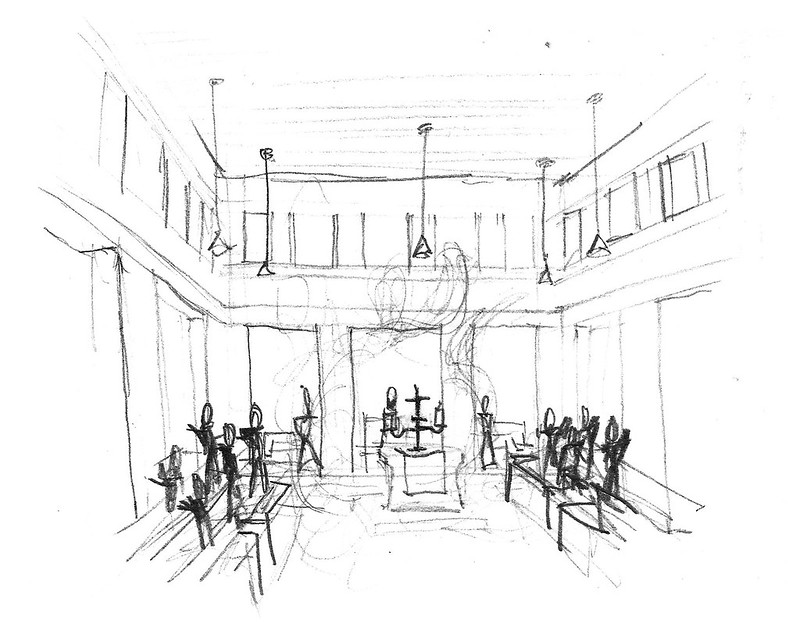

As the bells rang for Sext, the "principal work" of praying the hours began, and thus the principal role of the upper church. Here is the Benedictine liturgy in its archetypal form.

As a house of the congregation of Solemnes, Gregorian chant is treasured. There is definitely a resonance between the chant, one that goes beyond the experienced simplicity.

The offices had a special significance to me in that the first full day of my stay coincided with the Feast of the Dedication of the St John Lateran Basilica. This meant that all of the antiphons and readings referenced sacred space in some way. These will receive further attention in subsequent posts.

I cannot fully describe the impact and importance of time ordered by the offices.

+++ Refectory

Following Sext, the sacristan opens the cloister doors at the side of the church and the monks file out (bowing to each other and the altar).

The guests followed the monks to the refter (refectory) for the midday meal through the upper cloister to the second floor of the old cloister its star-sculpted vault, down the smooth bluestone steps inserted by van der Laan to yet another dramatic environment built from the same elements, configured for yet another distinct use.

In the refectory many subtle details work in concert to reveal the heart of the balance between the three form-worlds as they are interrelated within the monastic life. And this is truly my honest reaction and experience and not an analytical statement attempting to reconcile.

The foot of the table was the turning point in the experience. The monks and guests sit on benches (slightly taller than those in the gastenzaal) before single-sided tables circling the room. The tables have an angled return at the bottom, mirroring the table top, on which the feet rest. The effect on one's posture is a revelation. Sitting just removed from the ground (the tables themselves are an additional step up from the ground) heightens perception, one more physical and gestural act of "setting apart." The comfortable attention thus created in gesture suits perfectly the meal without speaking, listening to the words of the reader intone passages from the rule, lives of the saints, etc.

This is but one moment among many in the refectory: the procession from the church passing from cloister to cloister, down the stairs, and passing the particular sequence of carvings; the unique double height cloister antechamber; the massive and welcoming doors; the small rite of hand-washing by the abbot to welcome guests; the standing before the tables for prayers before and after meals; the details of the pointed rafters; the acts of serving and being served; the comforting warmth and earthy herbal flavors of the (unexpectedly, in my case) delicious midday meal; the intoning of the cantor, reminding of the continuous life of prayer; the hum of the kitchen barely audible, reminding of the continuous life of work; the view of the woods and hills to the south (downhill) from large vision glazing not found anywhere else in the abbey.

The refter is also a place where the older Böhm building most directly interacts with the van der Laan insertion. Elsewhere the two interact by addition, the seams intentionally and skillfully hidden. Or there is simply the furnishings in the existing rooms. But the south wall of the refectory has new windows, made clear on the exterior by the concrete sill and header detail. Dom Hans van der Laan was not fond of the "expressionism" of the earlier abbey, and yet this insertion is perfectly harmonious. There is, in fact, a family of material finishes throughout the abbey which compliment each other so that it is not the conformity ideal of, for example, Pawson's Novy Dvur. Perhaps van der Laan would have preferred the uniformity, but I think rather this harmony is a far more impressive feat and allows the life in the abbey to dominate the architecture.

It is, as it were, that necessary imperfection... wabi-sabi.

+++ Humility & Sentimentality

How quickly I was able to enter the rhythm of the abbey surprised me, though it probably was made easier by the fact we had been saying some of the offices at the conference and had done nothing but drive between churches between the two.

So now having worked, prayed, eaten, and slept according to the ordering of life, I began to reflect on some of the general aesthetic and cultural appeals of the romanticized spirituality of monasticism. Thomas Merton, or at least the attention paid him, is emblematic of this individualist (or even selfish) spirituality based on experience. We hear always about the importance of silence. But this is not quite right.

There can be no more authoritative voice on silence in the Benedictine life than The Rule: "The ninth degree of humility is that the monk restrain his tongue and keep silence, not speaking until spoken to." This is a matter humility, restraint, and obedience, and one amongst many aspects of a life of humility at that.

At one point I noticed a few people glaring indignantly, rolling their eyes so as to communicate (which should, I think, be counted as an infraction of the essence of St Benedict's humility of silence) and even shushing people talking quietly in the church between offices. Clearly their whispered (presumably) sharing of being in this space ruined someone else's ideal experience of silent perfection. Were the discussion inappropriate or unduly loud, it would be a different matter.

But I was reminded of the sound of spoons scraping bowls in the refectory. This was natural noise, the proper sounds of eating, and as such did not destroy the order of life in the monastery. My awareness of my footsteps, once I was settled into the routine, was only heightened when I was out of place–late for the morning office. But what is proper (natural) is refined and reshaped into the ordered life (cultural) and further transformed into signs which communicate not only for each other but for God (liturgical).

The forced sentimentality is so out of character with the actual continuity of monastic life. But I wonder if sentimentality is merely what we call sentiments we do not share? Or is there an objective criteria?

+++ The Mass

With Terce on the second day, we come finally to the completion of the upper church: the celebration of holy mass. With the tabernacle, side altars, confessionals, etc in the crypt, this upper church itself has only the functions of the mass and the offices (and their directly derived devotions). The control of the program is part of the abstraction and purity of the architecture. The church and the crypt two must be considered a whole, and really a whole with the entire abbey, and cannot be judged according to a parish church arrangement.

The mass truly completed the church. The placement of people, which seems perfectly natural and obvious in the space and not requiring any overt choreography, reveals further the proportions of the building and in turn accentuates the hierarchy of the assembled body.

In particular, the use of aisle/ambulatory behind the altar is perfect in a way that only a sacristan could achieve. The play of the aisle and the hall is in itself exquisite and perhaps the best proof of the more complex ideas in Architectonic Space which go beyond proportion as a systems of measures to encompass eurythmy and multiple scales.

The presbytery occupies the central portal. Unoccupied (as in the photos) it is oddly oversized version of the basic chairform used throughout the Abbey. But occupied, it gives the presider an appropriately profound presence without elevating him or excessively separating him from the two servers on either side or the monks in their stalls.

A credence table occupies the rear wall in each of the two side portals. The two servers are constantly coming and going with the objects and texts required for the mass. The brilliance here is that these actions reveal the work of the mass, perfectly framing these activities of service, without explicitly drawing attention to them in a way that would distract from the essential actions of the mass. In fact, I do not not know if someone not as biased towards concern with this aspect of the mass would even notice the coming and going. This is why I say that only a sacristan, who understands the work of the mass, as opposed to the mass as show, could design a space so perfectly fitting. Well-meaning designers, and I include myself here, want to engage the liturgy, but that generally means doing something conscious, something artistic. Composers fall into this trap as well.

Speaking of completing the space, the incense is the ultimate piece. Filling the space around the altar between the stalls, presbytery and congregation's benches, it becomes an ephemeral object encircling the altar. Thus the altar, and the entire building together with its inhabitation, finds its fullness, prepared for the celebration of the Eucharist.

I regret that was I unable to photograph the mass or any of the hours. A sign in the entrance made this request and I had no desire to try and sneak one in spite of my hosts. But it is incredibly unfortunate that I cannot share this with you, because the architecture, even more than I had expected, is woefully incomplete without the human body completed by the vestments, and to a lesser extent, the artifacts and incense. Of course a photograph would not contain the entire realm of ordered time: the chants, words, gestures. But it is less a desire to contain the whole expression of worship than to combat the reductive nature of photographs of warmly textured and softly crafted modern forms which is too easily misread.

At least the after-effects of the dispersed incense capturing the sun's rays and thickening the perception of the space helps a little.

+++ Asperity & Craft

The sun came midday on the second day of my stay. Multiple lighting conditions, indeed ideally multiple seasons, are necessary to fully experience any finely tuned building. And the breaking of the clouds allowed one of the most glorious moments of the trip. Following the monks out of the church after sext on the second day, we entered the upper cloister, suddenly awash in light, the plaster-coated brick walls transformed from muted somber weight to a bright white brought to life by its texture. The walls basked in a piercing blue sky and reflecting a lushly verdant garth, still damp, and the shimmering golden and amber autumn leaves of the woods beyond. I forgot even to regret not having a camera.

There are two stories told about the construction of the church and this texture which so beautifully animates the architecture. Probably both are apocryphal, but like all good persistent myths they still speak about the truth of their subject. Dom Hans van der Laan desired a particular degree of imperfection in the brickwork of the church. The more likely story about this was that he found one particular mason had the right sense of this imperfection and only he was the only one allowed to finish laying the columns. The more enjoyable story is that van der Laan encouraged the masons to drink a little more during their meals to generate the desired unevenness.

No matter the truth behind the asperity, it is one case among many wherein the building clearly reveals its making. This is an aspect to which only those versed in construction and detailing have full access, but its effects are universal. Other instances include the board formed concrete headers and beams and the clear fabrication of the furniture and its expressed ribbed structure. These are all expressions of craft, not of the abstraction and precision of Ando's concrete. Unfortunately these are subtle and difficult to read when not seen in person.

And of course we cannot discuss the craft of the place without referencing the stonework. Brother Leo invited us to visit his workshop the evening meal on my last day. What a treat!

(For more on the stone carvings and typeface, see this article.)

+++ Gesamtkunstwerk

The entire precinct of the abbey, together with the Rule it sustains, is like the ideal complete works of art. The architecture, vestments and habits, and liturgical artifacts were all designed together as a whole by a single author. But that is not all, for they were designed within a larger whole of a "designed" liturgical life. So it is a more complete "total work of art" than any design project could be, and more importantly it is not the work of a single author.

Therefore it is a gesamtkunstwerk not in service of the art, the work itself, or its artist. These were the faults with earlier 20th century attempts at gesamtkunstwerk, and in fact the entire modernist idealist projects. Insomuch as they were attempts to start over from nothing, they were each built on a single ideal and ego. They were built on an insufficient basis and built with insufficient complexity to withstand even a single generation.

St Benedict built his Rule of the experience of the desert Fathers and the life of the church. It was a different type of ideal order. And it has stood. And I believe it will continue to stand even as it becomes increasingly at odds with the culture it stands amongst and against.

+++ Ordering

To conclude, every aspect of the stay in the Abbey returned to the concept of ordering.

In van der Laan's terms, the cultural activities are principally acts of ordering, as we do not create from nothing but reshape and complete what we find revealed. Architecture is the delineation of ordered space out of boundless natural space. Music is the delineation of ordered time out of boundless natural time. In each of these cases, number, logic, and proportion are the root means for that delineation.

The Rule of St Benedict is a supremely complete delineation not only of time but of the whole of life. And the delineations made by van der Laan using the Plastic Number, are no more than a parallel order. Order this complete must be accompanied with submission and humility. And these traits are apparent to me in van der Laan's architecture, quite in opposition to the rational abstraction of architectures contemporary to him and similar in appearance. For all the numeric intellect, there is little rational about this architecture. But I do not think this can be seen outside of submission to the entire order of Benedictine life.

A little unexpectedly, this retreat did not leave me longing for this life, regretting my vocation, unwilling to leave the cloister. Rather, it left me able to understand better my own seemingly unordered life and vocation from observing and listening to this ordered life. Even in the muddled Sunday mass back at home it was easier to recognize the essential forms.

Perhaps that is the role of van der Laan's monastic architecture for those of us who do not share his monastic vocation. His order allows us to better understand space and the human action of giving order and measure to infinite space.

And so, as I continue to study Dom Hans van der Laan, I am particularly curious about van der Laan the teacher. How did he teach? How were his lessons received and employed? And what does he still have to teach us about the order of things into which architecture fits?