Praying the Stations of the Cross with Ellsworth Kelly

/Download an Order for the Stations of the Cross for use in Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin and continue reading for more information.

Last year (and coincidentally on the First Sunday of Lent), Ellsworth Kelly’s Austin opened posthumously at the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas in Austin. It was his first architectural work and realized with the participation of many collaborators, including Overland Partners and the Blanton. Austin is a culminating synthesis and a reinventing capitulation of Kelly’s magnificent career. For a more thorough examination of the building as a whole, I recommend the pair of essays in Texas Architect, one written by Murray Legge and one written by me.

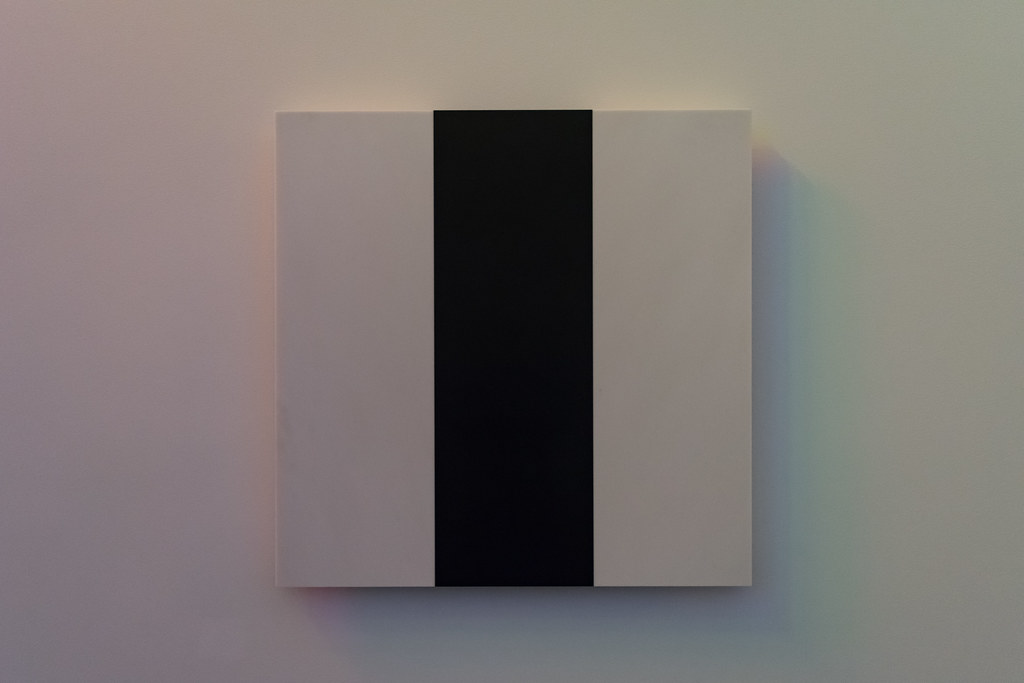

As a complete work of art, it comprises the building itself and three types of work that reflect different aspects of his œuvre rendered in unique materials to fit into the architecture: a tall wooden totem, three spectrum stained glass windows, and a serise of fourteen black and white stone panels.

Fourteen is an intriguing number for a series like this. It does not occur as frequently in culture as, say, sets of twelve. Neither does it divide quite logically into the cruciform bays of the building. (As it turns out, the geometry of the plan subtly deforms to accommodate the 3—2-2—2-2—3 arrangement of the panels and accentuate the procession from the entrance as well as the purity of the apse.) Before I was able to visit the building or learn very much about its design, the fact that there were fourteen panels was a good hint to what they were. That and the obvious architectural resonances with early medieval European church architecture. As it turned out, those resonances were both deeper and more conscious than I expected, as the exhibit that accompanied the opening brilliantly explained.

The fourteen panels are the Stations of the Cross, a narrative processional devotion that traces the Jesus’ Passion from his condemnation to being laid in the tomb. They are, as is clearly evident, not figural. Even knowing this, my expectation was that they would be along the lines of Barnett Newman’s abstract stations, which began as subjective meditations on grief/despair and grew to number fourteen indirectly. Walking into Austin for the first time it was immediately clear that this was not the case. They are precisely the traditional fourteen stations and clearly legible as each.

I knew I had to come back and pray through them to see if they worked. And for me at least, they more than worked, they revitalized what had been a somewhat tired and often formally distracting practice. As I often feel alienated and dismayed by the dismal quality of art in so many churches, I was grateful to have something that spoke in a language that felt close to my native tongue. They held new insights to a familiar devotion by the nature of their abstraction, their placement, and the interplay of their forms through the narrative sequence. It was astonishing.

And so to make this a more regular practice for myself, and perhaps share it with whoever else might inhabit the small overlap in the Venn Diagram that would enjoy it, I made short order for praying the stations with Ellsworth Kelly’s Stations of the Cross. It is a relatively short sequence that is intended to be relatively inter-denominational while drawing on the rich heritage of the church. (Ultimately, though, it was just my personal preference for a way to pray the stations; being a devotion and not liturgy, there is room for that.)

Click the image below to download and print. It is designed to print front and back on letter size paper and be folded in half.

Each station begins with the customary response followed by one or two lines from scripture related to the station (Knox Translation, of course). Then follows a brief excerpt from an already brief meditation on the stations by John Henry Cardinal Newmann. A series of prayers concludes the station; in many Roman Catholic forms, these are an Our Father, a Hail Mary, and a Glory be. For this version I chose the Our Father and the concluding prayer from Lauds and Vespers of Good Friday, which is more specific to the devotion, less associated with specific denominations, and includes a doxology for good measure. Each station then concludes with a response taken from the responses and antiphons throughout the Good Friday Divine Office and selected to reflect on the particular station in some way.

In selecting the texts, I worked from many resources and versions of the stations available but focused on choices that reflected what I saw in Kelly’s work the few times I prayed the stations there last year.

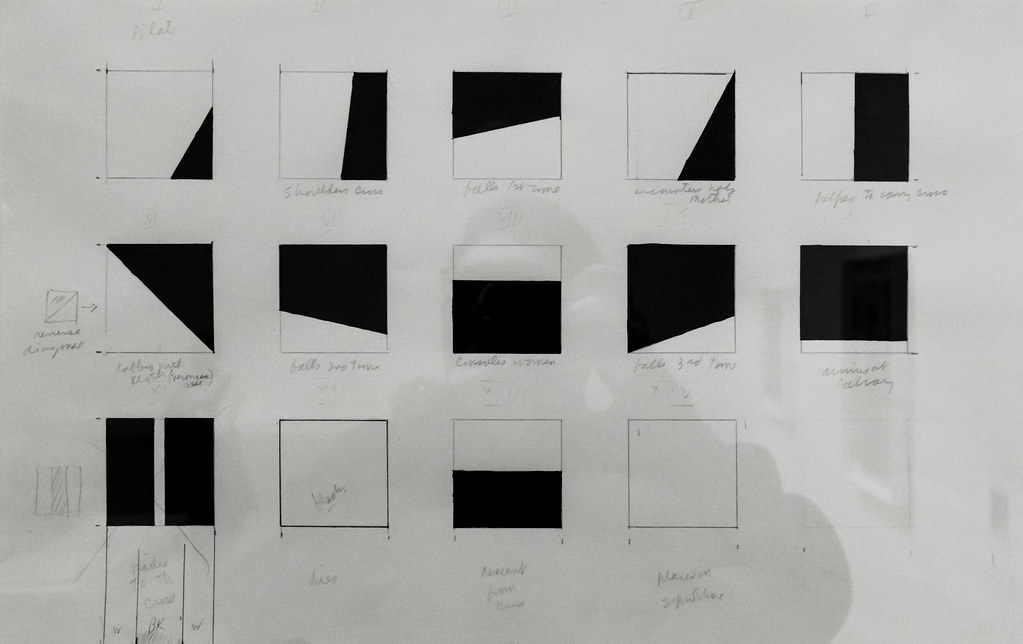

Kelly’s abstract canvases masterfully speak volumes with a clarity that few other minimalist artists approached. In researching his work for the Texas Architect essay, I was fascinated to discover that he based them on specific moments or memories of perceiving actual objects, which may explain some of the depth they contain. Consider, for example, this series capturing the spatial geometry of French Romanesque churches (exhibit view from the Blanton exhibit).

The genesis of the architectonic forms of Austin are clearly contained within these. And it is astounding that he was able to achieve not only the translation from the built form to this black and white encapsulation but to then retranslate it back into a physical object to be so similarly perceived.

Moving from the building through the panels and back enables the viewer to inhabit the Stations in a way that I have never experienced before.

The Blanton’s exhibit also included this original sketch for the stations (with notes for the few changes made for the final construction).

This sketch includes subtitles for each station that confirms that they are intended to correspond to each of the customary stations stations. The precise word choice Kelly used may reveals something about his reflection on each during the their inception and creation. (I decided to use these as the names of the stations in the order.)

The interplay of the stations with the colored light from the windows adds an incredible depth to pieces, as does the texture, finish, and translucency of the stone itself.

Certain formal patterns emerge as you consider the relation of the figure to the station with which it corresponds. For example, the three sequential diagonals of the three stations where Jesus fell, each one with the oppressive weight of the black field pushing further down, gives structure to the middle of the narrative. The same diagonal appears, rotated ninety degrees, at the start of the procession at station two.

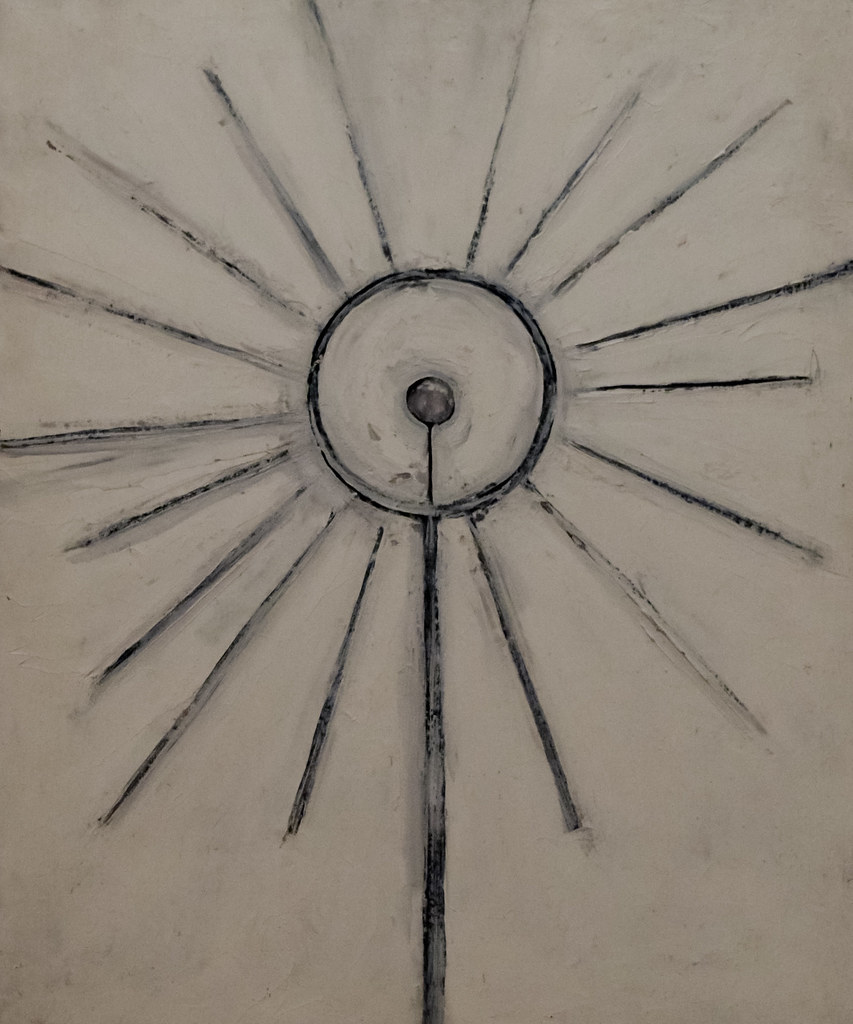

But what stands out to me the most is the set of stations where there is some “fellowship in his work,” as Cardinal Newmann calls it.”His merit is infinite, yet he condescends to let his people add their merit to it.” The parallels between V and XIII are explicit here in a way I had not previously noted. Similarly, this work forced me to consider the pairing of V and VI (Simon and Veronica) in new ways. It is not just the formal relationship, but the fact that the face each other at the ends of the north transept. Add to that their location next to a window in the form of a monstrance…

(And if you question whether or not that was the intent of the form, here is a canvas entitled Monstrance that Elsworth Kelly painted in 1949 that was the same exhibition at the Blanton).

The whole of Austin works on so many levels. It rewards repeated visits and any form of delving into Kelly’s art, be it analytical, poetic, or prayerful.