Outraged Christ and St Paul, Bow Common (Re)visited

/

Earlier this year I wrote about the massive found-wood crucifix by Charles Lutyens entitled Outraged Christ currently installed at St Paul, Bow Common in London. The conclusion was that this was an encouraging direction for liturgical arts, an appropriate and timely expression of the content, and an exemplar of art and architecture working in concert in the service of liturgy.

Fortuitous scheduling for travel to the Netherlands gave me 18 in hours in London on a Sunday morning. This meant allowed me to both participate in worship at St Paul, Bow Common (which I was not possible during my previous research trip) and to see the Outraged Christ sculpture in person.

Worship at St Paul, Bow Common

First, some thoughts on St Paul, Bow Common in use. On a personal note, having spent so much time studying, thinking and writing about this building (it was the subject of my (unofficial) Master thesis), immediately upon ducking under the corner of the portico to escape the rain, I thought to say, "hello, old friend." As a general rule, I do not talk to or anthropomorphize buildings, but in this case it is very hard not to. She has so much personality and vitality.

The vicar, Prebendary Duncan Ross, greeted me with a vigorous hug (he greeted everyone that way this morning) and the salutation, "welcome back to your church." And I thought at the time that it was odd to actually feel more welcome at a church I have only visited once before (and of a different denomination) than my own. And that is not just a reflection of academic and architectural familiarity.

Once again, my readings of the church based on the documentation proved themselves valid in experience. And then some. Specifically, the formal superimposition of spaces which facilitate the simultaneous expression of domus Dei and domus ecclesiæ (which are generally have contradictory material expressions) was further enhanced in the celebration of the liturgy. And the influence runs both ways: the material implications of the objects and space shape the postures, arrangement, and signification of the assembled Body of Christ and the particular local worship enlivens, completes, and gives more complex meaning to the building and its parts.

Speaking to a few parishioners afterwards about that particular local worship and its informal formality. They settled on the description "chaotic high church." This is wonderfully accurate and in many ways the best of all possible worlds. The celebration is full high church "bells and smells": generous incense, worthy vestments, intoned prayers, combined with hymns from the richness of English hymnody. At the same time, there was a casual coming and going, reminiscent of a family gathering more than anything else. But the centrality of the altar, together with its concentric spatial attending features (outer wall, peristyle atrium, lantern, paving changes, coronoa, steps, ædicula/ciborium), meant that the liturgy was always the principal aim and focus.

The balance thus achieved makes it difficult to fall into either the trap of self-important, hypocritically pious, fetishized religiosity on the one hand or the trap of self-satisfying, watered-down, humanist spirituality on the other.

The important ideas of "active participation" and a greater openness towards the liturgy have far too often found expression in adaptations of the liturgical celebration. But rather than bringing the liturgy down to the level of the people, as it were, our goal should be to bring people up to the level of the liturgy. (Case in point, although not the only method for its fulfillment, the phrase actuosa participatio originates in the interest greater availability, accessibility, and wide-spread use fo Gregorian chant.) This is significantly harder, as it requires that we not re-form the liturgy itself but rather re-form ourselves, our in.

At St Paul, Bow Common the community realizes this worthy goal through the balanced combination of a non-linear hierarchy of spaces distinct but not separate (architecture), a commitment to the continuity and tradition of worship not as an end in itself (liturgy), and above all in the context of an honestly joyous and welcoming attitude from the clergy and the assembly (community). And you could go on and list the further good work of the church outside the communal celebration as well.

In short, the celebration achieves in parallel the same confluence of domus Dei and domus ecclesiæ achieved by the architecture. The result is an elusive and remarkable balance to which we (regardless of style worship) would do well to aspire.

Outraged Christ, (Re)visited

Seeing Lutyen's crucifix in person likewise confirmed my initial impressions of the work, but the added concrete experience greatly increased my appreciation.

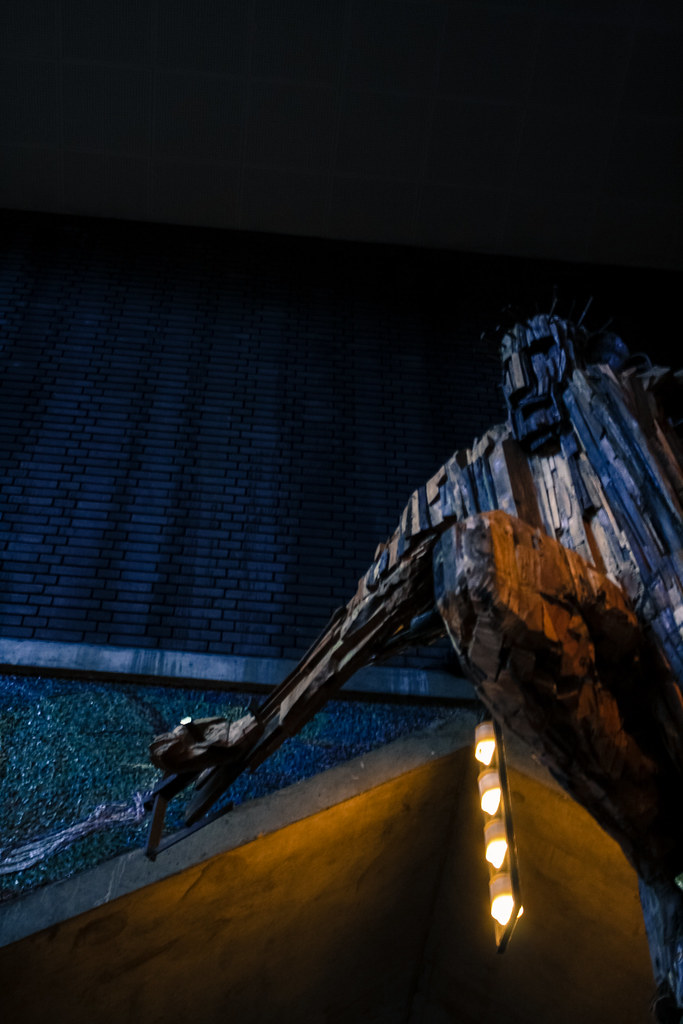

I did not anticipate its impressive weight and muscular presence. The scale of the work and the attitude of its posture, especially the unusual extended knee which hangs just over the viewer's head, makes it overwhelming and awesome. The propriety of the scale and proportion of the crucifix to those of the building further accentuates this impression. The vertical component mirrors and then develops the columns, while the horizontal echoes the horizontal wood of the benches. The horizontal also occurs within the realm of the triangular spandrels and angel mosaics (also by Charles Lutyens, 50 years earlier) so that Christ's head is at the level of the angels' heads.

There were many details revealed in the closer inspection. In particular, concavity of the chest seems to speak to the pain and depravity of the Passion. So too the withered right arm, which was uncovered from the remnant of another sculpture destroyed by the artist. The contrast between the two arms reminds of the dual expressions of the well-known Pantokrator ikon. Such a formal dichotomy is a great technique for increasing the signifying content of liturgical art and for expressing the important reality of paradoxes inherent in our attempts to communicate divine revelation.

The pained contortion of the left foot comes from the source material where the tree grew around a piece of steel. This element highlights the found-wood nature of the piece as a whole, a significant aspect of the rough and weak aesthetic that I feel reflects a critical expression of contemporary culture.

A the time of my visit, the crucifix was placed amongst the congregation's benches, in the corner left by the radial arrangement of the benches set in the rectangular atrium/nave. It would be possible, if difficult, to install this work as the principal crucifix in a church associated with the altar (often reductively compacted to the back wall). But it would be an impressive result.

Here it is a temporary addition which, as mentioned before, is extremely resonant. And the placement in the nave highlights the multiplicity of symbols of the Body of Christ present in the celebration of the liturgy.

It is truly a serious and exemplary work of religious and, moreover, liturgical art for our time.