On Christ & Architecture

/This week brought a number of notices about a symposium entitled "On Christ & Architecture" to be held 15-16 March 2012 at the Judson University Department of Architecture. The symposium aims to "provide space for focused discussion of the intersection of living Christian faith and the discipline of architecture." A definite highlight of the event is that Nicholas Wolterstorff will give the keynote address and moderate the discussions. I consider Dr Wolterstorff the foremost living voice in aesthetics—particularly theological aesthetics—even from my rather limited comprehension of his great Works and Worlds of Art.

Unfortunately I will not be able to attend, but I would highly recommend it to anyone who is able.

The title of the symposium raises an interesting question which may or may not have been intended. It is not "On Christianity & Architecture" or "On Faith & Architecture" or "On Christian Living & Architecture" or "On the Church & Architecture" or any permutation of words on the same theme that would more closely reflect the stated purpose of the event. The organizers specifically chose "On Christ & Architecture."

While I do not know the reasons for the choosing of this title, it prompted the following reflections in me.

Although generally aware of Judson University, I did not know its denominational affiliation. My guess, which was based solely on the title of the symposium, proved to be correct; the university's "About Judson" page describes the school as an "evangelical Christian university." (It formed out of a Baptist seminary.) To focus on the person of Jesus and to ask what his position on a specific topic would be reflects the evangelical tradition and comes from the same spirit as the WWJD phenomenon.

This is not a flippant criticism; although it approaches the ridiculous through over-misuse, the question of WWJD? remains a valid line of inquiry provided it is not used in isolation. It does carry the danger of an individualistic post-rationalization (making Jesus support what I've already decided), and it is a very poor basis for binding propositions. The results are particularly absurd when the subject at hand is anachronistic or a matter of taste. But with these limitations in mind, Christians do well to consider what Christ taught and apply it where applicable.

So the question posed by this symposium, or at least by its title, remains: "What does Christ have to say about architecture?" or "What would Jesus do about architecture?" An historical inquiry might tell us about the general attitude of his contemporaries on architecture, but we really want to know if there are any teachings of Christ in scripture that pertain to architecture. Did Jesus directly and explicitly address any aspect of architecture: the proper way to design, the value and meaning of buildings, architectural history or theory, how to practice architecture, the purpose or disposition of ornament, structure or materiality, proportion, sustainable building practices, or the matter of building styles (about which Christians are continually bickering).

Buildings do figure in to the discourses and descriptions in the Gospels. And all of the instances bear on only the one matter of the value to be placed on buildings, although "direct" and "explicit" might be a little bit too strong. The conclusion will potentially disappoint Christian Architects looking to Jesus to endorse the fruits of their profession. This is not to say that buildings cannot be an integral part of the missions Jesus tasked us with, but they are at least problematic.

The instances listed below are intended as more of a prompt than a conclusive analysis. I would be very interested in responses and additional quotes.

The Temple

For any discussion of architecture and the Bible, the obvious go-to topic is the temple. This is never as fruitful as architects seem to hope that it will be, but it is a good starting point here. The obvious reference concerns driving the merchants out of the temple and the associated claim of rebuilding the temple in three days (John 2.19). In Matthew 26.61, witnesses falsely accuse Jesus of stating that he will destroy the temple and rebuild it. But there are two problems here for our purposes. The first is that John goes the trouble of telling us Jesus refers to his own body here. The second consists of how much of the offense of the money lenders can be attributed to an affront to the building or an affront to the work it houses. We can at least conclude that the building demands some respect on account of the liturgy it serves.

This is a reaction to how things stand. The other significant reference Christ makes to the temple gives an image of the value of the temple in an ideal future.

"Believe me woman, Jesus said to her, the time is coming when you will not go to this mountain, nor yet to Jerusalem, to worship the Father. ... but the time is coming, nay, has already come, when true worshippers will worship the Father in spirit and truth; such men as these the Father claims for his worshippers. God is a spirit, and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth." (John 4.21-24)*

These statements do not preclude worshipping in Jerusalem (and by association the temple), but it does shift preference away from the physical and cultural aspects of worship in general. In the Old Testament, the construction of the temple is celebrated, but it is also treated somewhat as a concession much like granting the monarchy. The attitude expressed in the Gospel aligns with this latter attitude.

The Synagogues

What of Christ's attitude towards the local synagogues? Time and again Jesus prays and preaches there showing a respect for the cultural customs and the edifice itself. On the other hand, many of the notable sermons occur outside; even the most complete theological discourse became known affectionately as the "Sermon on the Mount."

From this line of reasoning, it would seem that there is nothing wrong with buildings, but by no means are they necessary.

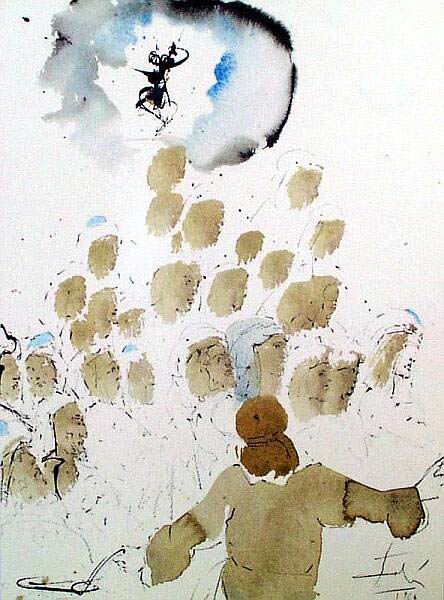

The Transfiguration

The transfiguration (Matthew 17.1-9 / Mark 9.2-8 / Luke 9.28-36) is that one moment in redemptive history when particular form has the greatest significance. There is not even consensus on whether what was seen was the result of created or uncreated light. (For the record, the west says created and the east, uncreated.) Either way what is seen is perfection incarnate, and Peter reacts verbally to it on behalf of humanity. We are left only to speculate on the reactions of the other two disciples as in the great icons of the Transfiguration.

"The Peter said to Jesus, Master, it is well that we should be here; let us make three arbours, one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elias; he did not know what to say for they were overcome with fear." (Mark 9.4-5)

Peter's plan is not carried through. God essentially ignores his panicked appeal to architecture, which we may attribute to a desire to make the experience permanent or show respect but either way it certainly directs towards the terrestrial realm, by pulling focus back to Christ transfigured. It is one of those rare and profound moments when physically-sensible sound waves carry the voice of God, the acoustic equivalent of the visual transfiguration.

The reaction (or rather, lack of reaction) is not to particular built form, but to a fundamental impetus toward architecture: the desire for permanence achieved through enclosure leading to monumentality. Peter's other reaction is fear. And if fear drove him to building tents, it confirms the association of dwellings with security. Peter had no idea what he was saying; his words reveal not an intellectual proposition but a pre-conscious desire. It is a possessive desire, more eros than agape.

As the architectural impetus here reveals more about humanity than its building practices, so too the lessons to be drawn from this text. One lesson stands out to me: do not become so preoccupied by the good work of building (which is really the work of dwelling, of sustaining, of seeking permanence, of pursuing legacy, of holding on to what cannot be held, or in the worst cases the work of financial speculation) that it causes you to miss the actual presence of Christ.

Residences

The interactions of Jesus with and in other peoples' houses might be another category to consider. One event in particular stands out in which Jesus calls a little improvised deconstruction an act of faith, giving more evidence to the argument of the devaluation of architecture in the Gospels.

"And now they came to bring a palsied man to him, four of them carrying him at once; and found they could not bring him close to, because of the multitude. So they stripped the tiles from the roof over the place where Jesus was, and made an opening; then they let down the bed on which the palsied man lay." (Mark 2.3-4)

Obviously this is nowhere near the top of the list of primary interpretations of this passage. And there we run again into the problem with this kind of inquiry. This passage only has architectural relevance when read by an architect. It is interesting as a piece of a larger hole, but one who use this as the basis of a theory of architecture would find themselves building on sand.

Again, this is all a rather cursory collection of reflections gathered over the past few years. They are not intended as ultimate conclusions or an exhaustive list, and I would welcome comments.

I have a similar collection of architectural or dwelling-based imagery in the Roman Rite (the most notable of which has but recently been restored to us in English) that I will most likely post here before too long.

*[The translations used here are by Monsignor Ronald Knox published in 1945]