John S Chase: Progressive Architecture in East Austin

/ For anyone with an eye for design who drives down Martin Luther King Blvd in East Austin, two unique mid-century buildings stand out from the neighborhood. One is a house (The Philips House, 1964) projecting from the hillside. The other is David Chapel, the Missionary Baptist Church across the street with its iconic tower and sharply ascending nave roof. Both have dramatic compositions dominated by low angular roofs which engage a steeply undulating stretch of the street, each in a different way. Like many examples of modern architecture, they present a dramatic presence when experience from a car.

For anyone with an eye for design who drives down Martin Luther King Blvd in East Austin, two unique mid-century buildings stand out from the neighborhood. One is a house (The Philips House, 1964) projecting from the hillside. The other is David Chapel, the Missionary Baptist Church across the street with its iconic tower and sharply ascending nave roof. Both have dramatic compositions dominated by low angular roofs which engage a steeply undulating stretch of the street, each in a different way. Like many examples of modern architecture, they present a dramatic presence when experience from a car.

I've always wondered about them. Like the vast majority of the countless people who drive by, I never bothered to look closer and discover their true significance despite their obvious quality of design. And now I know they are much more significant than I had guessed, thanks to the organization Docomomo US (Documentation and Conservation of buidings, sites and neighborhoods of the Modern Movement in the United States) and their regional chapter Mid Tex Mod (both of which I joined that afternoon). Its chapters, members, and related groups all across the country participated in Docomomo's Tour Day by visting significant examples of mid-2oth century architecture in 40 cities. The Connecticut tour visited First Presbyterian Church, Stamford (Wallace K Harrison's "Fish Church").

The Central Texas tour gave access to these two buildings on MLK, which it turns out are both the work of John Saunders Chase, FAIA, and included introductory lectures by Fred L. McGhee and Stephen Fox (who provided much of the information that follows below).

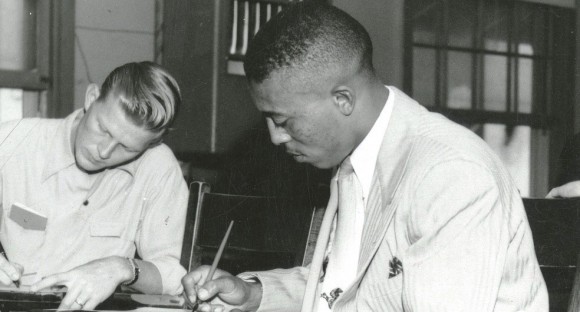

Chase enrolled at the University of Texas two days after the Supreme Court forced the desegregation of its professional and graduate schools. So when he completed his Masters in 1952, he was the first African American to graduate from the UT School of Architecture. This milestone was the first of many such firsts. Perhaps the most publicly significant was that he was the first African American to be licensed to practice architecture in the state of Texas. That honor was somewhat backhanded, however: with no architecture firm willing to hire him, he had to have the internship requirements waived. While this is not unheard of, and he did have some professional experience, it seems the state did not want to draw the attention to his plight.

After graduation, he turned down to a position to teach architecture in a newly formed school at Prairie View A&M. But accepting the position would have qualified the program to offer graduate degrees and would therefore have closed access to UT for other African American students under the state laws at the time. Instead he accepted a job teaching drafting at Texas Southern and started his own firm.

Working independently in Austin and then in Houston, John S Chase built a practice based on engaging the churches in African American communities, which he knew to be the heart of the community. Many of his major early works were churches, and these in turn led to business and residences from church members. It was not until well after the end of segregation that Chase began to receive public commissions, but once they started Chase made significant contributed to Houston's built environment. His firm eventually grew to three offices in Texas and worked on many large project collaborations, including George R. Brown Convention Center, Astrodome Renovation, and an unbuilt commission for United States Embassy in Tunisia. Chase designed much of the Texas Southern University campus.

Chase's influence in the profession had a national reach through his involvement in the AIA, as one of he twelve founders of the National Organization of Minority Architects, and as the first African American to serve on the US Commission in the Fine Arts. In that last role, he was part of the selection of Maya Lin for the design of the Vietnam Memorial, an event which has its own place in the history of peoples under-represented in architecture.

While there is not yet a full biography of Chase, following his death in 2012, interest has risen. If you are interested in learning more, an episode of the In Black America podcast (KUT), features recorded interviews with him in the 1980s. [The audio is currently available on the KUT archive site.] He has been profiled or mentioned in many places online: his Obituary in the Houston Chronicle, Texas State Historical Association Online, the Texas Architects, Diverse Education, The History Makers, and a mention of the tour on Architectural Record. His firm's archives are now maintained by the Houston Public Library Architectural Archives and a major exhibition is currently planned for sometime in 2015.

For his Master's Thesis, "Progressive architecture for the Negro Baptist Church," John S Chase designed a complete campus for a hypothetical church in East Austin. This was not a simple design project; it was an incredibly thorough study of the potential of an expanded program that would embody the full breadth of the importance of this type of church in its community. It was also remarkably detailed and data-driven in its approach to the church itself as an expression of the acoustic and visual criteria particular to the worship practices of a Black Baptist church. It may very well be the first such study for its denominational family, which had tended to rely on vernacular and borrowed forms in its structures. From this it is clear that Chase was not just an architect who designed churches, but someone who put concentrated analytical thought into the nature of church buildings.

I look forward to studying this project in detail (it is held at the UT Library), so expect a report on that here in the future. He also included references and influences, which will be an interesting insight into what was taught and read concerning church architecture at the time.

The David Chapel is considerably smaller than the ambitious program of his thesis project, but it does apply many of the individual ideas developed therein.

The nave rises westward from the top of the hill behind a low entrance. Some of the influence of Frank Llyod Wright claimed by Chase, shows in the narthex, especially in angular elements. The detail of the beveled glass joint between two angled planes stands out on the façade.

In a very clever spatial manipulation, the volume of the nave narrows as it ascends utilizing forced perspective to accentuate the ascension towards the focal wall. The height of that wall enables a clearly organized composition of the locus artifacts of the Baptist church: the pulpit front and center, the choir arrayed behind, and the baptistry high above, surmounted by a large plain cross.

The natural light increases from the lower rear portion upward to the pulpit and choir, reinforces the spatial progression and gives the front of the church an exterior quality. (In fact, I did not immediately realize that I was photographing the space with no artificial light.)

In its tectonic expression and openness, the tower has some affinity with Austin's iconic moonlight towers, the nearest of which is two blocks west on MLK.

The remainder of my flickr set of my photos from the event can be seen here.