St Bartholomew: Grace truly to believe and to preach

/Last week I began a six-week seminar on church architecture for UT FORUM. Part of the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, UT FORUM welcomes "anyone with the leisure time to enjoy learning from the many remarkable people in our community with expertise to share." It is predominantly retired alumni who make for an wonderfully perceptive audience well-versed in many areas. This is the second seminar for them of which I have been a part, and it is definitely a pleasure. The purpose of the first lecture in the series was to massage the conception of what constitutes architecture. This is done first by touching on the approaches to concepts of dwelling, art, and culture in Heidegger's "Building, Dwelling, Thinking," Adolph Loos' essay on architecture (1910), and introducing the first chapter of van der Laan's Architectonic Space. And then by reading the Christian scriptures in light of those concepts, perhaps as an architect might read the Bible as an origin myth for the creative act. Beyond the most literal stories about building (which are read primarily for what they say about the primal motivations for architecture), this reading reveals an emphasis on dwelling and presence, spatial metaphors, and the use of buildings as symbols in the Psalms and the Prophets. We didn't quite get to the brief section on the New Testament (brief because most of the New Testament content about the early church practice related to worship and buildings falls in the second lecture anyway), so the second lecture will start with the image of the Transfiguration.

I mentioned in passing the thing I often say (intentionally cryptically) that I have only experienced three church buildings with which I have been reasonably satisfied. Obviously all three will be included in the course, but this comment got a bit more response than expected. So I decided to rearrange them a bit, specifically to use one of the three—St Bartholomew in Manhattan—to both tie into the discussion of the Transfiguration and to continue the art-architecture discussion that also seemed to generate a lot of response and thought…and perhaps some angst. I was a little devious there, intentionally overstating, from Loos, that architecture is not art (except when it is). The intent was to over-emphasize the distinction in modes of perception, appreciation, and most importantly the carrying of meaning between art, architecture, engineering in order to then show in the rest of the seminar the absolute importance of their integration in architecture and especially in the church building, which I would argue, not only incorporates art into its architecture but in its monumental function (including its physical echo of the action of the liturgy) falls into Loos' exception. But if we look at church buildings solely as consciously communicating in the manner of art, we risk losing the pre-conscious mode of carrying meaning particular to architecture. Ultimately the potency of church architecture lies it its ability to embody symbolism in multiple modes, so understanding the distinction between those modes aids in appreciating the whole.

I can think of no better single illustration of precisely this integration of art and architecture than St Bartholomew, which means I needed to finally get around to processing and posting my photos of that church from my trip to New York last August.

What's so great about St Bartholomew? Why do I rank it among my top churches? It meets every abstract/gerenal criteria for liturgical architecture that I have ever required or considered (and most of those of others as well when they don't require very particular expressions) while at the same time speaking to me on a very personal and spiritual level. From general impression to minute details, every aspect of the church is a synthesis of contrasting ideas of church and art such that it confounds reductive categorization.

The architecture is the work of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, who from all accounts had a personality worthy of such a name. He certainly had the architectural chops, and oh could the man draw. He was highly regarded enough in 1930 to make it on the West façade of UT's Goldsmith Hall (School of Architecture) with the likes of Vitruvius, Ictinus, and Palladio, the only four names so venerated.

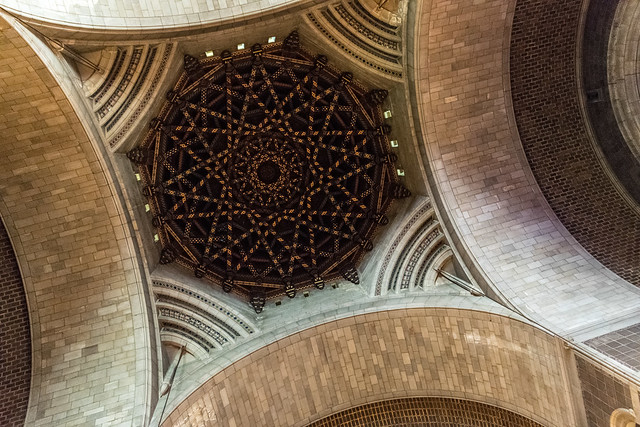

St Bartholomew was one of many of Goodhue's works completed by his firm posthumously. The most significant change to the design after Goodhue's passing was the insertion of the unusual dome. The dome is one of two elements I would complain about (in the entire building!) because it does seem slightly out of place. It looks fabulous, and from a purely visual perspective, fits beautifully. But there is something about its spatial impact that is slightly off in its proportion and intersection with the volumes of the barrel vaults. And it doesn't seem to relate to the chancel in a meaningful way that a dome implies. But the touch of woodcraft and structure is a welcome counterpoint to the masonry. (The other, more serious, complaint is the font in the baptistry, which incidentally is also the one piece that is not well-integrated into the building, though its placement and orientation is not without significance.)

Looking up at the dome reveals one of the architectural elements that gives the building a richness that is then able to incorporate its symbolic sculptural program. There are a number of different types of masonry incorporated in the structure whose differentiation express it structural and symbolic function. The juxtaposition of dark, rough brickwork infill with heavier stone masonry sets up a system in which finer stone and inlaid work in significant locations. The exterior exhibits a similar composition but with a more rough ashlar treatment. In other places, such as this side chapel covered in a series of shallow domes exposed Guastavino tile-work.

There are times when multiple materials like this leads to business and cacophony. (In the class I'm going to show the interior of Santa Maria del Popolo as a counterpoint to that effect and to St Bart's integrity generally.) Here there is a deep ordering and coordination resulting in a uniformity eschewing homogeneity. One of my criteria of church architecture is that it reward repeated readings, and a unity that can be appreciated initially as a whole but that gives way to its component parts as the eye explores over time, each with their own logic and order and beauty, exactly fulfills that criteria. Especially when the detail so revealed have both explicit and implicit symbolism.

Consider a gate to the baptistry with John the Baptist holding a lamb with the words "Ecce Agnus Dei" that represents both John The Baptist's function and overlaying it with the function of the celebrant at the elevation, thus uniting access to salvation as expressed through baptism/cleansing (washing with water) to access to salvation as expressed through eucharist/sacrifice (washing with blood).

As I work through the remainder of my New York trip photos, expect to hear more about Goodhue. Part of the delay has been my obsessing over his tomb and a little project it inspired.

The craft and practice of architecture is not just design but the coordination of crafts to result in a building which coordinates its components. Goodhue was a master of architecture in this sense, frequently collaborating with artists and craftspeople, notable the sculptor Lew Lawrie and the impeccable building artist Hildreth Meière. I would love to be able to delve into the nature of those collaborations more.

There is absolutely exquisite art throughout the building—predominantly the work of Meière and Lawrie—that falls into that junction of legible figural narrative and idealized abstraction absolutely critical to liturgical art. The art, like the architecture and the places as a whole, falls entirely in continuity with the whole tradition of the art and worship of the church while incorporating a particular and individual (even innovative or progressive) expression. As a result of this active continuity, this living tradition, any artistic innovation reinforces rather than overrides the core functions of the church; indeed, even more than for yet another poorly executed rehashing of familiar forms.

Further, the building-integrated art (for no piece appears to be an addition to the building, and even Loos might have trouble objecting to its inclusion) provides symbolism that only contributes to the collective and central celebration of the liturgy and the beauty of the environment without encouraging distracting diversions into devotionalism while still supporting individual religious experience outside the corporate worship.

One way St Bartholomew embodies the ideal of integration of art and architecture is through the harmony of the placement of artistically treated elements in the building with its content. A great example is this Mandatum tympanum over the entrance, of course, to the part of the building where the Mandatum is expressly carried out through social activities in works of mercy.

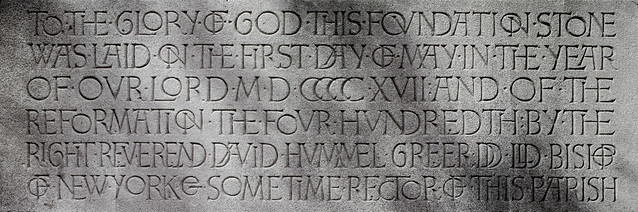

The building-integrated text at St Bartholomew is one of its characteristic elements that adds a compelling richness to the building, first of all because it exists. There simply isn't enough well-considered and well-executed building-integrated text. I do not know for sure if these designs are the work of Goodhue, but he was a skilled type designer in addition to architect. The distinctive letter forms have become part of the church's visual identity in their printed and web materials. But they are not all in a perfectly uniform style, changing based on the location and purpose (both of the text and within the architecture of the whole). The cornerstone seems almost playful and conversational without losing its gravity:

Something about that brings to mind the actual act and ceremony of laying the cornerstone in a way that most simply report the the date and facts in a static and disinterested manner. Like the other two on the top three list, I find myself involuntarily talking to this building.

Looking up and to the right from in front of the cornerstone, another string of text begins at the top of the portico:

The portico originally fronted the previous building. It was added by Stanford White (of McKim, Mead & White) to the earlier James Renwick-designed Romanesque church. That photo confirms that the text-infused parapet is an addition by Goodhue, since it now needs a top to stand alone in front of the church. It could easily have been a repetitive pattern, but the words add a dimension of meaning to the façade and unite the pre-existing structure with the rest of the buildings, especially with the capitals on the interior. The chosen text is the Collect for the feast of St Bartholomew (as it appears in both the 1662 and 1928 BCP):

O ALMIGHTY and everlasting God, who didst give to thine Apostle Bartholomew grace truly to believe and to preach thy Word; Grant, we beseech thee, unto thy Church, to love that Word which he believed, and both to preach and receive the same; through Jesus Christ our Lord.

It is rich and complex, pulled directly from the liturgy. It is not just a dissociated word or phrase that communicate only vaguely inspirational ideas which, no matter how important, serves no more than a reminder of the existence of the concept. (However, wise placement can make an economy of letters quite effective when it is read spatially in the context of the celebration: for example, the "GO YE" on the back wall of St Martin, Austin, which is itself a reference to the liturgy referencing in turn Jesus' words in the Gospels and read as the assembly turns and processes having just heard a parallel exhortation as the conclusion of the service.) As a prayer for the church, it fits the exterior of a church. There is a humility to it supplication that the church would do well to express more often publicly. It cannot be consumed in a single reading, from a single point of view. In that, it reminds me of the portico of St Paul, Bow Common (also on the short list) with Ralph Beyer's setting of the Locus Iste text around three sides.

All of this comes from carving the activity of the building's inhabitation (the words of the liturgy) into the stone itself. The words are the primary signs of the liturgy; it seems logical they should carry through its other signs.

The actions of the liturgy already (should) carry through the spatial disposition of the building. Of all the spatial symbolism at play in this building, the strongest and most dominant is the apse. Being of Anglo-catholic persuasion, the chancel is well-defined as more distinct than separate, a worthy goal for any sanctuary.

The subtlety of the chancel's clear spatial distinction without too great a degree of separation comes through a balance of every architectural element at play: harmony of the chancel to the other space and the proportions of the chancel to the whole space; the acknowledgement of the difference between vertical and horizontal dimensions of space; lighting; material; ornament and symbolism; and the apsidal mosaic as an elevated terminus of the building.

As I have discussed elsewhere, the terminal focal plane or space of a Christian church is an interesting problem. In temple-type worship, there tends to be a single object of devotion toward which the architecture also directs. While the Christian church has a central focus (usually the altar, but more generally a sanctuary), it is rightly conceived more as a space than an object. For while Christianity uses and venerates images and objects as symbols to aid in, inspire, and direct worship, it does not worship objects themselves. And it is good for sanctuary arrangements to maintain this clarity. One way the church clarifies the role of signs as signs is through the multiplicity of overlapping signs. Thus we end up with this condition where Christ is the priest, is the sacrifice, is the place where the sacrifice is offered, and is the one to whom the sacrifice is offered! (cf. Hebrews 9)

Spatial models that embrace these overlapping symbols tend to make for better termini of church buildings than planes of objects. And one of the best candidates is the semicircular apse, as borne out by its use from the earliest purpose-built church buildings. The use and the content of the apse has differed over time, but its core spatial symbolism remains.

The apse does not terminate a space in a single point (corner) or plane, but returns the space back upon itself. Rudolf Schwarz relates his Fifth Plan, the "Sacred Cast" that represents the goal of the "Sacred Way," or the linear processional model of spatial assembly, to the ancient apse. "Opened wide, heaven is waiting. The Lord, sitting at the front, stretches out his arms toward the train of people." He the apse "opens up an eternal vista, then to return once more out of eternity."

Concave shapes are used consistently as symbols of heaven. Concavity expresses both enclosure (even embrace) and directionality. It is appropriate then that apse mosaics and murals have consistently been used to depict scenes of heaven such as the heavenly liturgy or Christ resurrected and/or glorified. If the proper orientation of Christian worship is in a common direction through Christ to God, then a version of this combination of spatial and figural signs of heaven makes an ideal candidate for the focal terminus of a church building.

St Bartholomew's apsidal mosaic (the work of Hildreth Meière) contains a depiction of the Transfiguration. While not a literal depiction of heaven, the event itself was a revelation of heaven through the the signs of God's presence (in the cloud, in the voice), the communion of saints (with Elijah and Moses), and Christ's glorified body. The Transfiguration is not only fitting as an image of heaven, but also as a model of the validity of images of heaven within the realm of creation. There is another Transfiguration on one of the double capitals with great details that emphasize the heavenly aspects.

One detail of the Transfiguration narrative that I find interesting from an architectural perspective is Peter's response to seeing Moses and Elijah conversing with Jesus. It is the primitive urge to build in response to seeing the manifestation of God's glory.

We can view our work of church-building (both in the architectural sense, but more importantly in the more broad meaning) is carrying out the work Peter wanted to do (without understanding what he was saying) and later began. Once again, we discover with St Francis and as in every instance of architecture in the Bible that the building is not the end in itself.

The Transfiguration teaches us that Church-building is (a) a response to God's revelation of (b) the full identity of Christ in his glorified body through (c) a primal urge to create (d) despite hardly knowing what we're doing (e) to prolong or celebrate or monumentalize the outpouring of God's grace (f) by honoring, elevating, and worshiping Christ (g) and venerating his prophets, servants, saints while (h) enacting that part of the dwelling-with-God possible in this age while (i) directed toward its fullness that is our ultimate end of enjoying God's presence forever. But even this does not exhaust the functions of churches or church buildings!

The greek word rendered as "arbors" here is σκηνή (skēnē) is the word used in the letter to the Hebrews to signify the Old Testament tabernacle that bears record to the covenant as well as dwelling places generally and even a place of worship dedicated to Moloch. Its use suggests a desire to both make the moment last and to honor three figures. But it also implies a dwelling-with, the more intimate and immediate presence. The Tabernacle of the Old Testament and the extension of its image in worship bring together the absolute awesomeness of the manifestation of God's glory with the promise of dwelling (being-in-place) with His people, the promise of the restoration of the original condition of creation and our ultimate end.

The three tabernacles surface in the floor of the chancel in the form of three church buildings: Canterbury Cathedral (Cantuaris), St Peter Basilica (Roma), and Hagia Sophia (Constantiopolis). That they are removed from the actual scene establishes that this symbolism is commentary. That they exist on the floor associates them with the realm of human activity.

The choice of the three churches reflects the "Branch Theory" popular at least among the high-church Anglicanism (especially the Oxford Movement) whose spirit exudes throughout St Bartholomew. These three buildings represent each of the three main branches of tradition in the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church, namely the Anglican, Eastern Orthodox, and Roman Catholic. Obviously this leaves some significant portions of Christendom out, and the idea has never taken hold in its more legalistic application. But in a more broad sense, it is similar to other expressions of ecumenism (especially if we read Cantuaria to stand for Protestantism generally). Perhaps it is not entirely catastrophic if, like Peter, we don't understand what we're doing and we end up failing and dividing. There is can be hope in that "the mystery of Christ is so unfathomably rich that it cannot be exhausted by its expression in any single liturgical tradition. The history of the blossoming and development of these rites witnesses to a remarkable complementarity." (CCC 1201) Which is not gloss over the very real distinctions between churches and actual questions of validity of traditions. It is precisely why distinctions are more important than differences.

For this church at least, these three churches provides a key for interpreting the unique amalgamation of influences that is St Bart's. The influence of the architectural and artistic traditions of all three branches are clearly recognizable throughout the entire fabric of the church.

And we've only looked at a few specific details of that fabric! I haven't even touched on the chapel at all:

I have been railing against the importance of taste in a still-unpublished set of posts on some buildings I appreciate that most real people (non-architects) almost universally despise (soon, I promise!). But I can't ignore the role of taste in my appreciate of St Bartholomew. Ultimately I value it highly because it works on so many levels, ones I would classify as universal, as traditional, and as personal. With a little self-probing reflection, there are definitely characteristics common to what I currently consider my "three favorite" church buildings. Some are more conceptual and explicitly liturgical, such as a clearly articulated liturgical arrangement combining a hierarchy of spaces within a unity of space. That is the ideal of distinction without resorting to separation. All three are genre-defying in their continuity (romantine? byzantesque?); they confound people who insist on viewing "Modern Architecture" as rupture and forcing a false dichotomy between "modern" and "traditional."

But there are also some specific architectural strategies common to all three: a general darkness and resulting in dramatic (and purposeful) focal lighting; stately proportions and substantial walls; rough-textured brick reflecting hand-crafted-ness; building-integrated text; strong Byzantine influence; an "exterior" character to the interior space. These are not things I consider necessary to church architecture, but for me they go a long way to contributing to what is essential.

This post has been a little more personal than usual. So much of my appreciation of the churches on these pages has been in somewhat of a detached mode (of course I am not detached is not the case when actually celebrating in these churches). It has been a while since I have given much room in writing to simply delighting in a work that I truly enjoy and reveling in its beauty.