Veiling Images in Lent

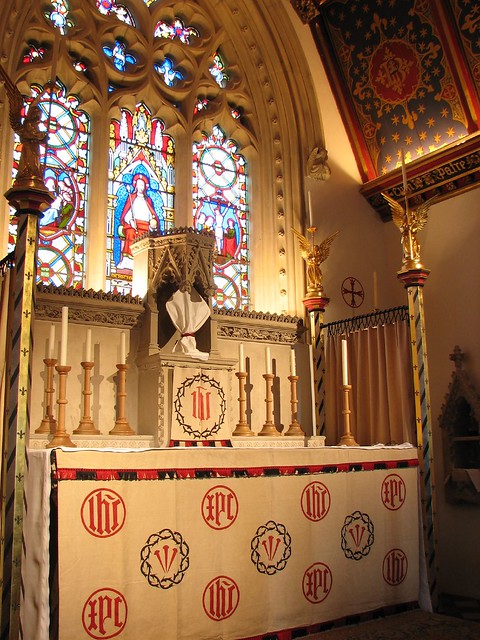

/At some point during Lent, many Christians will walk into their churches to find the statues and images covered in cloth veils. The practice of veiling images is a centuries-old tradition based on a variety of different practices and continues today in different ways in different countries and denominations. In most Roman Catholic parishes who observe the practice (which is optional, as is generally the case), they will appear this weekend, prior to the fifth Sunday in Lent at the start of Passiontide. This year, my own parish veiled images for the first time, partly because I volunteered to construct the necessary materials. This means I spent a good bit of time this Lent reflecting on the images and what it means to cover them for this time. Similar to other recent posts, this post will consider both the principles behind this aspect of material liturgical practice and some practical aspects of how it was done.

Why veil images? As with any liturgical practice, there is never a single reason why something is done. Liturgical signs are meaningful as liturgical signs because they draw forms from the best of nature and culture(s) combined with divine inspiration (if not outright institution) and religious Tradition. Christian symbolism is better considered as a system of signs each with a synthesis of overlapping meanings based on the growth of religious practice.

Reading various sources you will find a broad range of many different explanations of the practice. Most are passable appeals to a single reason based on reflections on the penitential or somber character of the season of Lent, though some are ridiculous. The award for the most absurd goes to an image found online that says it is because Jesus was disfigured during his Passion. This is incorrect on a number of levels, first of all because we would be hiding that which is in fact the very subject of the season of Passiontide itself, that which we should now be focusing on more than any time during the year. It also points to a superficial and sentimental kind of devotional concept of religious imagery. More deeply, it denies the place of suffering, pain, and ugliness in the Christian understanding of beauty in general and in particular the beauty of Christ in light of his Passion, which is, again, the very subject of the season leading up to Holy Week.

Veiling images has a long tradition in the Christian church. We'll look later at a related practice that dates at least from the ninth century, and mosaics from the earliest centuries of the church suggest veils hung from ciboria around the altar. But I came across a very interesting historical depiction of the practice in Pieter Bruegel the Elder's painting The Fight Between Carnival and Lent of 1559.

For a bit of context, Bruegel lived in the midst of intense political and religious conflict following the Reformation. Personally removed from those conflicts (he worked for both Catholic and Protestant patrons), he is an acute observer of the world they created. The mock battle in this painting is not Catholic versus Protestant, but rather the contradictory extremes in popular and religious practices brought under scrutiny in the context of the reformation (read Andrew Graham-Dixon's column on the painting for more).

A fascinating image in many regards, of particular interest to our discussion is its depiction of contemporary Lenten practices on the right side of the painting which will seem

For example, eating fish:

Giving alms:

Pretzels and clackers:

And of course, of interest to the present subject, veiled statues seen through the open door of the church:

Liturgical Function of Images

In light of other penitential practices of Lent, it makes sense to think of the veiling of images as visual and devotional fast. But to understand the significance of such a fast, it is first important to understand some of the purposes of the things from which we abstain. For many churches, the inclusion of images in worship is an unusual and uncomfortable practice, so veiling the images would be even more bizarre. A complete discussion of sacred images, the various types, what makes for good images, and the different iconoclasms throughout history is well beyond the scope of this post, but such images serve many purposes. The more individual devotional functions seem to overwhelm in practice and also provide for most of the objections; both supporters and detractors often misunderstand what they use or protest. Suffice it to say that sacred images in a Christian church are never objects of worship in themselves; they point to spiritual realities beyond themselves and beyond even the subjects they depict. Thus any worship of the object itself is supremely disordered.

But even the devotional use of sacred images is a secondary function. When in the context of the liturgical space—itself a sign with the special function of unifying the entire system of signs that constitute the liturgy—sacred images form part of the eschatological function of the image that is the church. Liturgical imagery unites our earthly worship with that of which it is a foretaste and a participation: the heavenly liturgy. In some cases this is quite clear; the apse mosaics of many ancient churches bear this out with different depictions of Christ glorified. San Vitale, Ravenna is an excellent example of this as well as how images of the saints, angels, and figures or events from scripture serve liturgical functions along with catechetical and devotional functions.

The inclusion of angels and heavenly beings indicates that these are images of un-image-able spiritual realities and establishes the context of the heavenly worship to which the earthly worship is joined. Lunette mosaics outside the apse, and thus flanking the space of the altar, depict the sacrifices from the Old Testament (above, Abel and Melchizedek). These are types of Christ's sacrifice and provide a commentary on the multifaceted nature Eucharist. Indeed, they are named by some Eucharistic Prayers. By pointing toward the sacrifice of Christ, they further point toward the redemption through Christ and its ultimate end of our sharing in God's presence. Similarly, the presence of saints from the age of the church model a more full and perfect participation in the worship of the church. But as they have also gone before into the perfect liturgy of heaven, their depiction is that of their glorified bodies. (This is why a degree of figural abstraction and idealized form is preferable in liturgical art.)

Thus the images of the saints in churches established visually what the words of the liturgy proclaim when we sing "…with all the hosts and Power of heaven…" and pray "…in communion with those whose memory we venerate." Further, their purpose aligns with the request for "us, also, your servants, who, though sinners, hope in your abundant mercies, graciously grant some share and fellowship with your holy Apostles and Martyrs…" Certain types of images make these functions more clear than others. But even more important is the placement of the images and their integration with the space and buildings.

For reference, the Latin Rite's General Instructions of the Roman Missal includes the following concerning sacred images:

#318. In the earthly Liturgy, the Church participates, by a foretaste, in that heavenly Liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem, toward which she journeys as a pilgrim, and where Christ is seated at the right hand of God; and by venerating the memory of the Saints, she hopes one day to have some share and fellowship with them. ¶ Thus, in sacred buildings, images of the Lord, of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and of the Saints, in accordance with most ancient tradition of the Church, should be displayed for veneration by the faithful and should be so arranged so as to lead the faithful toward the mysteries of faith celebrated there. Care should, therefore be taken that their number not be increased indiscriminately, and moreover that they be arranged in proper order so as not to draw the attention of the faithful to themselves and away from the celebration itself. There should usually be only one image of any given Saint. Generally speaking, in the ornamentation and arrangement of a church, as far as images are concerned, provision should be made for the devotion of the entire community as well as for the beauty and dignity of the images.

Liturgical Function of Images in Lent and Passiontide

If the liturgical function of sacred images is to focus on the eschatological aspect of the church's worship, what does it mean to suppress it at the end of Lent? And is it fitting? Part of the purpose of liturgical times and seasons is to direct attention to different aspects contained within its totality. The lens through which we focus on the action of the church shifts and some of its expressions changes, but the core of that action remains the same.

In Lent we fast from things which in themselves are good gifts of God in order to focus more intently on their giver and appreciate them more. And we are reminded of our unworthiness to receive those gifts in preparation for the annual celebration of the divine act that renders us worthy. In our worship, we forego expressions of joy and the fullness of God's glory by suspending the Gloria and the Alleluia before the Gospel. In Lent we reflect on presence through absence.

Veiling images that represent the fullness of God's glory and images of the heavenly worship in which all the saints in glory participate is precisely analogous to omitting the Gloria. One shift of focus of this season is an emphasis on Christ's humanity: the sacrifice inherent in the Incarnation and the sacrifice that is the Passion. Of course the constant totality of the liturgical celebration never allows us to lose sight of Christ's divinity, without which the Incarnation would not be a sacrifice and the Passion would lose its efficacy. So veiling images of Christ's glorified body, Christ victorious, and Christ risen, along with images of those who are now in his presence, helps enact that shift.

Veiling images also unites their secondary devotional function with the liturgy of the season. It is fitting that in the time that we celebrate both the institution of the Eucharist and the sacrifice it remembers, we focus on the centrality and primacy of the Eucharist celebration. Veiling devotional images in a church leaves the reinforces the visual centrality and primacy of the altar together with the sanctuary and the appurtenances directly required in the corporate worship of the church.

The use of veils, generally

The religious use of veils and similar cloths generally provides further explanations of the attitudes veiling images inspires and communicates.

At a very basic level, the veils provide simplicity. The veils used are generally simple and unembellished. In some uses they are unbleached linen; in others they are solid violet to be unified with the vestments and paraments used for the season. In either case, they do not draw attention to themselves. The value of asceticism in religion is unquestionable. While some are called to observe it for life, periodic doses are invaluable for all. Veiling provides a visual expression to accompany the other Lenten practices of fasting and abstinence.

In the reduction of the individual images to their basic plastic profile anonymity. The individual attributes that identify the particular individual represented are obscured. Veiling in this sense has the same effect as a uniform in deemphasizing the individual in favor of the collective. In some cases a single emblem on the veil hints at that identity, not unlike insignia on a uniform. These are often the means of their death, especially with the apostles and martyrs. But the uniform directs focus toward the body of Christ over its members, and ultimately to its head.

One religious attitude expressed by veils is humility. The intentional simplicity of the veils and the suppression of the individual remind us of our place. The veils hide both the representations of the glory we will share in the future and the material beauty of our cultural achievements (at least in those cases where the images are in fact worthy artistic artifacts).

Replacing festive garments with rough, unadorned cloth is an expression of penitence. The Old Testament bears this out repeatedly while also reminding us (in the Ash Wednesday reading from Joel, for example) that it is not the outward appearance of penitence that is important but the posture of the heart. We do not veil to make ourselves sad and sorry, we veil to reflect our collective interior attitude.

Penitential garments are also related to those worn to express mourning. The church's expression of mourning the death of our Savior begins its most profound expression with the stripping of the altar after the Mass of the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday in preparation for Good Friday. The visual austerity of the season within the sacred space reaches its peak, and some churches will veil images at this time. (The rubrics of the Latin Rite specify this moment, if it has not already be done.)

We may also see a parallel for the veils in the various shrouds and burial cloths used in preparation bodies after death. Burial cloths play a role in the Passion narrative. They also figure into the one of the Gospels account of the Raising of Lazarus which is read on the fifth Sunday in Lent, the day in the Roman Catholic church when the veils most commonly appear. This is also the text associated with the final Scrutiny for those who are to be baptized at Easter. So the imagery of death exchanged for resurrection and of (penitential) burial cloths exchanged for baptismal garments is certainly in the air at the start of Passiontide. We all die to rise again with Christ—as did all the saints—through baptism. Thus it is also fitting that the veils are removed for the Easter Vigil and its celebration of baptism that unites the death and resurrection of the neophytes with Christ's resurrection.

The veils also represent hiding and obscurity. In L'Année Liturgique, Dom Prosper Guéranger relates the veiling of the images to the Gospel read (at that time, prior to the reform of the Lectionary) which concludes with Jesus hiding himself and going out of the temple.

Everything around us urges us to mourn. The images of the saints, the very crucifix on our altar, are veiled from our sight. The Church is oppressed with grief. During the first four weeks of Lent, she compassionated her Jesus fasting in the desert; His coming sufferings and crucifixion and death are what now fill her with anguish. We read in to-day’s Gospel, that the Jews threaten to stone the Son of God as a blasphemer: but His hour is not yet come. He is obliged to flee and hide Himself. It is to express this deep humiliation, that the Church veils the cross. A God hiding Himself, that He may evade the anger of men - what a mystery! Is it weakness? Is it, that He fears death? No; we shall soon see Him going out to meet His enemies: but at present He hides Himself from them, because all that had been prophesied regarding Him has not been fulfilled. Besides, His death is not to be by stoning: He is to die upon a cross, the tree of malediction, which, from that time forward, is to be the tree of life. Let us humble ourselves, as we see the Creator of heaven and earth thus obliged to hide Himself from men, who are bent on His destruction! Let us go back, in thought, to the sad day of the first sin, when Adam and Eve bid themselves because a guilty conscience told them they were naked. Jesus has come to assure us of our being pardoned, and lo! He hides Himself, not because He is naked - He that is to the saints the garb of holiness and immortality - but because He made Himself weak, that He might make us strong. Our first parents sought to hide themselves from the sight of God; Jesus hides Himself from the eye of men. But it will not be thus for ever. The day will come when sinners, from whose anger He now flees, will pray to the mountains to fall on them and shield them from His gaze; but their prayer will not be granted, and they shall see the Son of Man coming in the clouds of heaven, with much power and majesty [St. Matt. xxiv. 30].

Sanctuary Veils

In addition to veiling people, there are many relevant traditions of using cloth to separate sacred space. The great precedent pertaining to the Christian salvation narrative is of course the veil enclosing and separating (keeping sacred) the Holy of Holies in the Tabernacle and later in the Temples in Jerusalem. It was this veil, a single piece woven of cloth red, blue, and purple cloth, that was torn open at the crucifixion.

The earliest extant mosaics depicting altars with ciboria include altar veils hung from them, though it is not clear at which points in the celebration (or in the seasons) these were closed and opened, if they were operable.

Father Edward McNamara also recounts a possible origin in a practice known from at least the ninth century Germany of veiling the sanctuary with a "Hungertuch" or "Fastentuch" (see his column here and make sure to read the update). If I say "tuch" means cloth, those terms should be easy to figure out in English. More information on this practice, which survives to this day in both Catholic and Protestant churches, can be read in this translation of Fr Joseph Braun's Die Liturgischen Paramente, 2nd ed., 1924. Note that this source says these veils were drawn back on Sundays and other solemn occasions.

These veils were painted with the scenes or instruments of the Passion. While not the same simplicity we expect today (devoid of all digital representation), the change in materiality and content follow the same principles described earlier. The contrast between the veil and what is covered has the same relative effect within the visual environment established by the church building. It is impossible to separate liturgical images from their context and usage and retain their meaning, which is why it is important to focus directives and explanations on the intent of a practice, especially when its form varies.

The Hungertuch generally takes the form of a large single cloth covering part or all of a permanently installed altarpiece.

Here is another German (Bavarian) variant with painted veils throughout the church:

Note that the veils are painted with scenes of the Passion, not representations of the images behind them; that detail was missed in some discussion I read online and otherwise would be rather silly to cover and image with an image of the image.

The first of the three examples (where from this angle we can see both the veil and what is veiled) represents both the greatest degree of disruption while also remaining the most harmonious with the church. It achieves an admirable duality that most fittingly incorporates the breadth of appropriate expressions with a powerful single move.

On the subject of different practices, the Lenten Array of the Sarum Rite is still used in Anglican and Catholic churches in England. It looks quite different from the purple cloths more common elsewhere. Here the veils and frontals used are made of rough and undyed cloth with simple insignia pertaining to the passion in red and black. And they are generally hung from Ash Wednesday. The quality of unbleached raw cloth has a more visceral appeal to the themes of penitence, humility, and asceticism of Lent. So in places where the custom survives or in Rites where ash is used or permitted as a vestment color in Lent it is a good option.

Here is one example of a Lenten Array in the English tradition:

However, taking a step back, we see this rather odd amalgamation:

A number of other examples can be seen in this flickr set.

Current Roman Catholic Practice

So there are a number of venerable and long-standing traditions of veiling images. But in the case of a Latin Rite church in the US introducing (or re-introducing) the optional practice, and in the absence of a venerable tradition, what is to be done?

Since the 17th century, the veiling of images in the Latin Rite has been confined to Passiontide, the last two weeks of Lent beginning from the Fifth Sunday in Lent. There a number of good reasons for this. While the veiling of images (or of the sanctuary) has much in character with the season of Lent, it directs even more specifically to celebration of the Passion and the veneration of the cross. Prior to the 20th century reforms, the Fifth Sunday of Lent was called Passion Sunday, and the prayers and readings from that Sunday turned from more general penitential themes to be directed more toward the preparation for the Passion. We saw this in Guéranger's description of the Gospel for that Sunday, when Jesus hides himself from public view. His next public appearance in the Lectionary would then be the Entrance into Jerusalem. Although the Lectionary has been revised and the literal application lost, this general motion remains that we turn in preparation for the Passion.

Veiling at the Fifth Sunday of Lent also fits within the larger rhythm of the season since it occurs after Lætare Sunday, so named for its Intriot:

Rejoice, O Jerusalem; and gather round, all you who love her; rejoice in gladness, after having been in sorrow; exult and be replenished with the consolation flowing from her motherly bosom. I rejoiced when it was said unto me: "Let us go to the house of the Lord."

This Sunday, with its more joyful propers, rose vestments, and reprieve from floral abstinence, is a momentary pause between the first four weeks of Lent and the final two (we might think of Passiontide as an overlay on Lent). To have the images suppressed the week after Læatare Sunday drives home this change in the attitude of the Liturgy.

Along with the rubrics in the Roman Missal, Paschale Solemnitatis (full text here) is the current document governing the observance of Lent and the Triduum. It includes the following statements:

26. The practice of covering the crosses and images in the church may be observed, if the episcopal conference should so decide. The crosses are to be covered until the end of the celebration of the Lord's passion on Good Friday. Images are to remain covered until the beginning of the Easter Vigil. (c.f. Roman Missal, rubric "Saturday of the Fourth Week of Lent.")

57. After Mass [on Holy Thursday], the altar should be stripped. It is fitting that any crosses in the church be covered with a red or purple veil, unless they have already been veiled on the Saturday before the fifth Sunday of Lent. Lamps should not be lit before the images of saints.

The USCCB initially declined to decide on the matter after the publication of this document, but, according to a statement by the conference (and the only document I have been able to find with specifics):

On June 14, 2001, the Latin Church members of the USCCB approved an adaptation to number 318 of the General Instruction of the Roman Missal which would allow for the veiling of crosses and images in this manner. On April 17, 2002, Cardinal Jorge Medina Estevez, Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments wrote to Bishop Wilton D. Gregory, USCCB President (Prot. no. 1381/01/L), noting that this matter belonged more properly to the rubrics of the Fifth Sunday of Lent. While the decision of the USCCB will be included with this rubric when the Roman Missal is eventually published, the veiling of crosses and images may now take place at the discretion of the local pastor.

That version of the Missal (Editio Typica Tertia) has now of course been published and does indeed include the instructions in the rubrics of the Fifth Sunday of Lent. (The full text of this statement has been reprinted in many places, and can be read here.)

On the execution of the practice, this document explains:

While liturgical law does not prescribe the form or color of such veils, they have traditionally been made of simple, lightweight purple cloth, without ornament.

Violet or purple is the color of the season in the Latin Rite. In places where there is a strong continuity to a variation and where that variation would be readily understood (for example, a Personal Ordinariate parish or a parish with a strong historical Bavarian heritage), there could be a strong case for deviating from the Latin Rite norm since it is not prescribed by law. But it is definitely a case where introducing a traditional deviation on a whim or for novelty would be a discontinuous application of a particular tradition instead of embracing a continuity with Tradition. Personally, my high-church Anglophilia would have loved to veil in Sarum-inspired Lenten Array, and I had other requests to use red or black cloth because that was what the petitioner grew up with. So in the absence of a shared and valid tradition in the parish, we deferred to the what is given as the standard Latin practice in the US.

The idea of red veils has merit since we have argued that veiling is tied to the Passion, and scarlet vestments are worn for Good Friday. If the option for veiling after the evening mass of Holy Thursday were followed, this makes sense. But the rubrics seem to indicated that the fullest expression is veiling for all of Passiontide, and the color of the season is violet, even though red and white are both worn on specific days during that time.

In various secondary sources, there is also reference to the idea that the stations of the cross and stained glass windows are not veiled. Both of these make practical sense, especially with the since the stations are used in public services throughout this time.

In my local parish church, the stations are stained glass, for what it's worth. But I recommend NOT doing this in the future, since it makes it difficult to use them after sunset. You end up just looking at dark squares in the wall and the images may as well not be there.

Veiling the Altar Cross?

But there is one detail of the practice that is unclear and I think merits some specific consideration: veiling the altar cross. The rubrics prescribe that crosses are covered until the end of the celebration on Good Friday. It is easy to read that statement alone and assume it refers to all crosses. But in the context of these very important celebrations of these two weeks and their rubrics, veiling the altar cross introduces some discrepancies. This question is not resolved in my mind, but here are some of the considerations involved.

According to Father McNamara, to whose direction in these matters I have come to defer: "The altar or processional cross is not veiled and, indeed, its use is implied in the rubrics for the solemn Masses of Palm Sunday and Holy Thursday" (source). Unfortunately he does not elaborate more. It is of course possible to process with a veiled cross, as is frequently done, but it is not clear that this is foreseen by the rites. But the processions involved are not simply processions, they are some of the most significant: the Solemn Entrance on Palm Sunday and the procession to the Altar of Repose on Thursday are processions par excellence. To lose the full expression of their prescribed liturgical imagery for the sake of a secondary optional practice seems disordered. This idea that the Triduum is the liturgy of liturgies, that Easter is the Sunday of Sundays, is a major part of my questions about veiling the altar cross.

It definitely has been done and is done. The passage quoted from Dom Guéranger earlier includes the altar crucifix as among the images veiled ("Everything around us urges us to mourn. The images of the saints, the very crucifix on our altar, are veiled from our sight. The Church is oppressed with grief."). The majority of photos of churches with veiled images seem to also veil the crucifix, so that appears to be the norm in practice among the admittedly traditionalist-minded congregations who predominantly retain the custom. And as mentioned, the practice can and does vary.

The centrality and unity of the altar are strong characteristics of the revised Latin Rite. The requirement of an altar cross is part of that emphasis:

Either on the altar or near it, there is to be a cross, with the figure of Christ crucified upon it, a cross clearly visible to the assembled people. It is desirable that such a cross should remain near the altar even outside of liturgical celebrations, so as to call to mind for the faithful the saving Passion of the Lord. GIRM #308

It is clear from the General Instruction of the Roman Missal that the altar cross is an essential component of the altar. So it would be odd to celebrate mass for those two weeks with so central a component hidden. Now of course veiling it does not make it cease to exist (I have matured to the point of achieving object permanence), and I appreciate the nuances of meaning that come from obscuring something so important. In Guéranger's interpretation it is exactly that oddness that is the point.

But on the other hand, it is not just that there are two weeks of Eucharistic celebrations with the altar cross hidden, it is those two weeks where the union of the sacrifice of the Mass and the sacrifice of the Passion is most perfectly expressed. Above all, it means celebrating the very institution of the Eucharist in an environment which is non-typical to the general celebration of the Eucharist. Paschale Solemnitatis and the forms of rites themselves (for example, the specific form of the Roman Canon for Holy Thursday) make it abundantly clear that the liturgies of the Triduum are the fullest type of all other liturgies.

Consider also the rubrics for stripping the altar following the Holy Thursday:

RM 41. At an appropriate time, the altar is stripped and, if possible, the crosses are removed from the church. It is expedient that any crosses which remain in the church to be veiled.

There are two reasons in the rites for veiling or removing the altar cross at this time. First, there is no celebration of the Eucharist until all is restored at the Vigil. Second, the requirements of the cross for veneration on Good Friday state that there should be only one cross and that it should not have a corpus. Again, the unity of the symbol is very significant to the rite. (PS 69. Only one cross should be used for the veneration, as this contributes to the full symbolism of the rite.)

Because the GIRM views the altar cross as more a part of the altar fittings covered in #308 (and less part of the images covered in #318), veiling or removing it as part of the liturgical action of stripping the altar more closely reveals its nature.

The idea of hiding the crucifix so that its imagery is more potent on Good Friday still applies in the veiling of the proliferation of that image. At the same time, it reinforces the idea that veiling the more devotional images helps to focus on the liturgical celebrations and the centrality of the Passion to the Eucharist.

Veiling all peripheral images and crosses while leaving the one altar cross unveiled seems more in line with the range of meanings conveyed by the practice and more in line with the full intentions of the celebration of the liturgies of highest significance. On this I may be entirely wrong (and would be very interested to additional information), but lacking any more definitive directions at this time, we left the altar cross uncovered at the Fifth Sunday of Lent and will cover it (since it is not easily removed) when the altar is stripped following the Mass of the Lord's Supper on Holy Thursday.

How to veil images (or at least how I did it)

From a practical standpoint, actually executing the practice of veiling images is tricky because the veils need to be custom-made for each statue or picture. Only covering some of the images doesn't achieve the intent of the practice and creates an unintentional hierarchy. It entirely defeats the purpose of focusing on the liturgy if people are trying to figure out why some are covered and others not, etc.

Step one was to seek approval of the local pastor. The parish has a liturgy committee, who supported the idea, and permission was obtained. For each season, the Arts and Environment team drapes cloth from the trusses that match the liturgical color of that season. We were fortunate to have sufficient material left over from this to construct all of the veils from the same fabric, which meant both the color and the degree of draping (is there a technical term for that?) would match.

And here is where I skip over quite a bit of internal hemming and hawing about the precise shade of violet to use. We have a mismatch in our sacristy between more red-violet vestments and more blue-violet paraments. It is like fingernails on a chalkboard during Lent and Advent, since the two meet, but that is a challenge for another time.

For the statues, my plan was to construct a fairly close-fitting piece over the top and about a quarter of the way down the back and then use magnets sewn in to the open ends to close the veils and produce some drapery. I used muslin mockups in situ to get the dimensions of this cap and a rough idea of how the drapery would fall.

The goal was to strike a balance between something that is fitted enough to be clean but loose enough to not look like a shrink wrapped person. Too tight makes the result a bit creepy. And having a bit of drape helps express the connotations specific to cloth mentioned earlier.

Marking and unfolding the mock ups gave a pattern that looked something like this:

The asymmetrical outline comes from the angle and position of the head and needing extra room on one side for an elbow. It also gives the piece a bias to start twisting, since one edge is longer.

Here is the installation of the magnet closures:

Here is the final result of the same statue (St Jude) shown in the mock-up above where the effect of the rotation is evident.

The shape of the draping comes from the underlying structure of the statue. The nimbus around our Guadalupe statue creates a symmetrical outline, so the drapery there is straight instead.

Here is St Joseph finished. This one required a pleat made by folding the cloth under the magnet (rather than sewing it in). This makes it a little easier to adjust when placing the veil.

For the frame pictures the challenge was to devise a system that would attach to the frames without requiring additional hardware or damage to the walls or frames. They would have to be reusable and installed and removed easily at height. The church has two 5 foot by 12 foot framed images on the front wall of the church hanging almost 30 feet from the floor and a smaller more accessible one in the back.

I cut the fabric wider than the frames and sewed magnets in the corners so they could be wrapped around behind the frame and stuck to metal strips on the back of the boards. This gives a much cleaner look to the edge and helps the fabric hang more flat.

My solution was to attach the veils to a 1 x 4 that would slide behind the top of the frame. Hopefully the weight of the board and folding the cloth over the top of the frame would hold it in place. If not, I had small clamps ready that could be used to hold the wood to the frame. As it turned out, the boards fit very tightly between the frames and the wall and held there quite firmly, so no contingency plans were needed.

The large frames are actually 62 inches while the fabric I had to work with was 60 inches wide. Oops. But I wanted to tie the form of those veils to the drapery hanging from the trusses because they are at about the same height and very prominent. So I stitched a longer panels to the widen the final piece and pleated it at the top so that the side panel would fall in a similar way to the ends of the truss drapes.

Testing the fall of the cloth:

Initial installation:

The finishing touch is a small card, in English and Spanish, to explain the veils for those who may not be familiar with the practice and are accustomed to praying near the statues.

Here is the text used for the signs, which attempts to summarize the reasoning and the details of the practice:

From the Fifth Sunday in Lent, the church may veil images representing the paschal glory of our salvation. It is a “visual fast” that directs our attention to the centrality of the Passion in our liturgy represented by the altar crucifix which remains uncovered. We unveil images before the Easter Vigil when "things of heaven are wed to those of earth" and we celebrate with the saints in glory Christ’s glorious Resurrection.

A partir del quinto domingo de Cuaresma, la iglesia cubre con oscuros velos las imágenes que representan la gloria Pascual de nuestra salvación. Esto es un "ayuno visual" que dirige nuestra atención durante nuestra liturgia hacia la centralidad de la Pasión, representado por el crucifijo del altar que queda descubierto. Quitaremos los velos de las imágenes antes de la vigilia de Pascua cuando "el cielo se une con la tierra" y celebramos con los Santos en la gloria la resurrección de Cristo.

And the overview of the final result: